Jazz musician Jackie McLean was on a bus when he opened a

paper and read that his friend, the great alto saxophonist Charlie

Parker, had died. In Robert Reisner's The Legend of Charlie Parker,

McLean says,"I had to get off that bus. I didn't know what

street, but I walked down it crying." Local jazz fans felt the same way back in 1972, when they

learned of the closing of Lennie's-on-the Turnpike. Last August,

friends of the beloved jazz club held a tribute at the Unitarian

Universalist Church of Marblehead honoring the twentieth anniversary

of the club's closing. The evening felt like early autumn. A

dry cool breeze swept broken clouds across the moon as over three

hundred people filled the Mugford Street structure, a hundred

more than the famous club could hold on its busiest night. Lennie

Sogoloff himself was there, with his wife and many family members.

Jazz clubs come and go, and in their passing, they leave longings

for those who love jazz. I've witnessed jazz in many famous clubs

- Birdland, Sweet Basil's, Pall's Mall. Most are blessed by big

city locales. Jazz is an urban music. But Lennie's, in West Peabody,

squashed between a trailer park and a truck rental company, was

the greatest club of them all. As a college student in the early sixties,-I learned about

Lennie's by tuning my radio to Norm Nathan's "Sounds in

the Night." Norm would refer to Lennie's as a "real

night people place." The first time I entered tht club,

Jimmy Rushing took the stage and sang, "St. James Infirmary."

I was hooked. What made Lennie's so memorable was not just the music. You

hear jazz masters in all the better clubs. Nor was it the low-ceilinged

intimacy. Jazz is often presented in cramped, unembellished rooms.

It was Lennie himself. Just as a coach's spirit can lift a team,

or an historical period may be linked with one man's greatness,

so Lennie's personality fused sound and setting into something

truly transcendent for those who were drawn, week after week,

to the room. Memories of Lennie's linger like the unheard melodies on a

Grecian urn. I remember Miles' muted horn and his dark, brooding

presence as he stalked the room between sets. And I recall Monk,

long after midnight, seated on a bar stool just staring into

space. Charlie Byrd's rhythms come back to me, soft sambas over

fugues and Beatle songs. On a slow night, Lennie would take a

seat during the final set. I can see him with his arms crossed, listening entranced while Kenny Burrell paid homage

to Ellington or Charlie Shavers, nearing the end of his life,

blew the old songs so sweet and mellow. The Marblehead tribute featured many of Boston's top artists.

At ten thirty, Lennie was called to the stage. An unassuming

figure with thick glasses and slightly arched shoulders, Lennie

"rapped" with three hundred of his closest friends.

Easy. Relaxed. First names. Witty anecdotes. The give and take

of soft-edged barbs. You see the punch line coming, but you laugh

anyway because this is Lennie. At one point, he spoke solemnly

of treasured friends lately deceased. Stan Getz - the week in

'66 when Stan recorded a live album at the club, and later said

he had enough for three albums, "two of music, one of applause."

Joe Baptista - Lennie's club manager during the prime years.

If Lennie was the melody, Joe was the rhythm, the solid foundation.

Lennie began a reminiscence about Joe, but then his voice became

wistful and trailed into silence. Joe died in October 1991. Lennie switched tempos. People used to wonder how he fit all

sixteell pieces of Buddy Rich's band onto his tiny stage. Simple,

he'd tell them. Remove three front tables and set up chairs for

the reed section. Three tables. Four chairs each. Twelve customers.

"But don't worry," Lennie would explain, "there

aren't twelve people alive who can outdrink Buddy Rich's Band."

Laughter. "If there are," he'd say, "give me their

names, and I'll book THEM." More laughter. Someone in the crowd yelled something about chili, and Lennie

said, "I'll handle the jokes." Guffaws followed. The

audience was his. I thought of the Andre Dubois story in which a divorced father

takes his kids and new girl friend to Lennie's for the Sunday

matinee. The girl friend tells the kids about Lennie's Mexican

cook who "makes the best chili around." Lennie used

to joke about "an old Mexican lady," but the truth

is that Lennie brewed the chili himself in the basement of the

club, where the musicians often warmed up. I worked for Lennie

briefly, and one of my jobs was to run the chili from the basement

to the bar. There'd be open trumpet cases and sheet music on

the concrete floor and guvs blowing up and down the scales. All

this, while huge pots of chili bubbled on the stove.

In Marblehead that night, Lennie kidded about the church setting.

At its birth, jazz was scorned by  church

folks as secular music, church

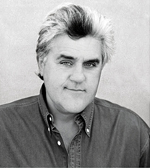

folks as secular music,"Joe Baptista- Lennie's club manager during the prime years . . . " Left to Right: The late Joe Baptista and Lennie during the moving of the original club to accomodate more parking. December 1963 perhaps inspired by the devil. And yet, for this night, the irony was fitting. In those long ago days, I would leave the old club, moved and deepened in some profound, wordless way, my soul soothed by reservoirs of sound. For me, a night at Lennie's was always more than entertainment. The place was sanctified, and Lennie was its holy papa. Kerry Brown teaches in Danvers and has been published in Living Blues, North Shore Sunday and various educational journals. UPDATE NOTE: 9/27/2006 (Salem Evening News/ Tom Dalton -- staff writer)  The voice on the telephone sounded familiar, but it wasn't a voice anyone expected to hear on a Monday morning at Salem State College. "Hi, this is Jay Leno," the caller said. Once the crowd in the Central Campus recital hall got over the shock, they listened and laughed as Leno talked for 20 minutes about his old friend Lennie Sogoloff, who gave the late-night comedian one of his first big breaks in show business. Sogoloff, 82, the former owner and operator of Lennie's-On-The-Turnpike, a legendary jazz club on Route One in Peabody, was being honored for announcing plans to donate his memorabilia to the archives at Salem State College. Sogoloff, who lives in Salem, and a guest panel were discussing the history of the club, which operated from the mid-1950s to 1972, when the surprise call came in from Leno. Only Sogoloff and a few others knew that Leno was going to take part in the morning program. When he was a young, unknown comic, Leno went to Lennie's-On-The-Turnpike in the winter of 1972 and asked the owner if he would consider allowing a comedian to perform. The club, after all, was known for featuring jazz greats such as Miles Davis, Dizzie Gillespie, Buddy Rich and Stan Kenton. Sogoloff had Leno audition right on the spot and hired him to perform on February 19, 1972. "Lennie started him on his career, and Jay Leno has never forgotten," said Jay McHale, the Salem State English professor who organizaed Monday's program. |