|

J.O.J. Frost called Marblehead "the best place on

Earth to live" and once said he did not think there was ever a

person who thought more of the old town and its people than he did.

In 1922, when he was 70 years old, Frost became an artist because he

wanted to preserve what he knew of Marblehead history. During the last

six years of his life, he completed about 130 paintings and 40 wood

carvings -- but he could not sell any of his paintings, not even for

50 cents.

Today he is considered an important native artist. Frost paintings sell

for several thousand dollars, and examples of hsi work hang in many

American museums. In 1953, the Smithsonian Institution included Frost

paintings in a traveling exhibition of American native art on European

tour. Three of his works were on view this spring at the Whitney Museum

in New York.

Born in Marblehead on January 2, 1852, John Orne Johnson Frost went

to sea as a young man, first aboard the fishing schooner Josephine in

1868 and then aboard Oceania in 1869. When he married Amy Anne Lillibridge,

who was known as "Annie," Frost gave up fishing.

For the first time, he worked as a carpenter's apprentice before joining

his father-in-law in the restaurant business. (Lillibridge's restaurant

was one of the first in town to sell friend clams.)

After a lengthy illness, Frost retired in 1865 and joined his wife in

raising sweet peas and flowers for which she was famous, selling them

to the well-established summer community in Marblehead.

Annie and J.O.J. were very much in love and when she died in 1919, J.O.J.

was grief stricken. Although his son and daughter offered to keep house

for him, Frost preferred to live alone. After a time, his basic optimism

prevailed and he was again tending to his garden, cooking and keeping

friends busy and entertaining visitors with his beguiling stories.

But J.O.J. still felt empty. To fill the void left by Annie's death

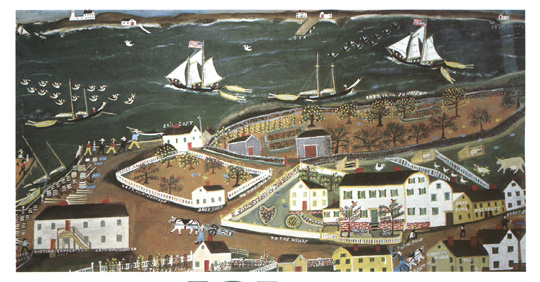

and to help preserve Marblehead history, he took up painting. Using

any materials at hand, Frost created pictorial stories of old Marblehead

and scenes from his early life at sea. He branched out into making wooden

models of ships, buildings, birds, and fish. He even modeled the "flakes,"

or the drying racks that once lined Marblehead's shore and were used

to prepare salt cod.

J.O.J. Frost is known as a folk artist because he painted for the common

person rather than the wealthy and cultural elite, and although Frost

attended no art school and never studied the principles of perspective

and color, he understood how to use stylized forms, design, pattern

, and a directness in which subtleties are absent. Frost was not concerned

with depicting Marblehead history formally. Rather, he gave it his personal

interpretation.

One charm of folk art, and Frost's in particular, is the lack of pretense.

The works have no heavy overlay of deep psychological meaning and no

abstruse illusions to past artists. Instead, there is an innocent clarity

similar to a child's art, which can often be ruthlessly honest.

Frost does not disguise the fact that he is educating his audience.

His fish carvings were labeled with the specie's name and his paintings

include captions for events or landmarks. His simple lettering showed

where fish fries were held, where flags were raised, and where roads

and buildings were in the old days.

Folk artists commonly pay close attention to detail, making their work

a valuable source of historic information. Frost's art, for instance,

reveals such practices as how to shoot coot and how a fisherman had

to stand up in a dory to defend himself and his catch from the sharks

that would appear alongside. In his journal, he described the latter

activity, saying "you have to hit the shark over the head and numb

him when he comes in -- you've got to know how to stand so the dory

won't tip over -- then the sharks would get you."

Folk art is most often a rural phenomenon. The urban artist tends to

swim in the mainstream, while the rural folk artist (and Marblehead

could be considered rural in those days) paddles happily along in a

side tributary, usually oblivious to the fact that there even is a mainstream.

Frost probably did not know that Impressionism was already 50 years

old, that Matisse and the Fauves, Picasso and Cubism had passed by,

and that Surrealism was in its heyday. Such styles would have been of

little concern to an artist interested in just depicting the past.

Often, Frost pushed his paintings around town in a wheelbarrow and tried

to sell them for a quarter or fifty cents. He would put a few in Litchman's

store but everyone thought Frost was peculiar and did not appreciate

his work.

One time, when Frost had one of his paintings in the window, some of

his old friends in town told him they wished he wouldn't show that picture

in public.

"Why not?" he asked.

"Because," they answered, "it only makes people laugh."

"Well," he said, "if that picture of mine makes people

laugh, it is serving a very useful purpose. So I guess I'll let it stay

right where it is."

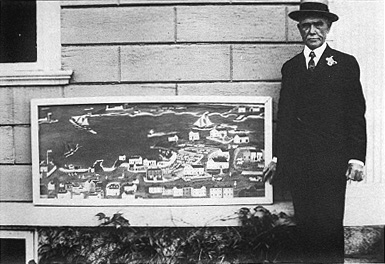

In 1924 Frost built a small structure behind his house at 11 Pond Street,

where, for the admission fee of 25 cents, a visitor could see his works,

his collection of Marblehead memorabilia and Indian relics, hear his

stories of old Marblehead and listen to his musical rocks (rocks that

made sounds when struck by a hammer.) Frost was always happy to play

the rocks although he became perturbed if the listener failed to recognize

the tune.

Frost distributed a handbill to announce the opening of his "museum"

on August 13, 1924, and indicated that all proceeds of that day would

benefit the Marblehead Female Humane Society.

According to popular account, no one came. Thereafter, however, the

museum attracted many visitors. For the msot part the visitors came

to hear the famed musical rocks. In fact, the drummer from the Hotel

Brunswick Orchestra in Boston even came to record the sound of the rocks.

These piles of musical rocks were destroyed by a housing developer's

bulldozer in 1966 when the former Frost land was sold for house lots.

Fortunately, some of these rocks were saved and are owned by people

currently living in Marblehead.

Frost must have known what people thought of him and his work, but characteristcally,

he was not bothered by ridicule and continued to paint.

The dapper, eccentric, and independent J.O.J. Frost died on November

3, 1928. During his last years, he had difficulty holding a brush. Often

he forgot to eat and sometimes fainted at his easel. He finished his

last work just a few weeks before he died. His gravestone at Waterside

Cemetary in Marblehead is surrounded by lily-of-the-vally, his favorite

flower.

The story of what happened to Frost's works after his death might have

brought a smile to the old man's face.

His son Frank inherited the collection and gave 80 of the pieces to

the Marblehead Historical Society in 1929. There, they were put into

storage and virtually forgotten. In 1938, a three-week exhibit of some

of the paintings was held at the Jeremiah Lee Mansion, home of the Historical

Society. In 1940, Arthur Heinztelmann, then president of the Marblehead

Arts Association, organised an exhibit of town memorabilia and used

a few of Frost's paintings. The paintings were so well recieved that

the Historical Society put some on permanent display at the Lee Mansion.

In the summer of 1943, Mr. and Mrs. Albert Carpenter, on a visit to

Marblehead from Boston saw Frost's paintings and arranged to meet his

son Frank to buy several of the works. As an art historian, Mrs. Carpenter's

interest in Frost's work must have been apparent to Frank, because when

he died in 1947, he instructed that his father's  pictures

be sold to the couple, which they were. pictures

be sold to the couple, which they were.

In 1948 the Carpenters arranged for an exhibition of Frost's work at

the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston. The show was well received

and marked the beginning of a broader recognition of Frost as a 20th-century

native painter.

Meanwhile, in 1952, Mr. and Mrs. Frederick D. Mason bought 11 Pond Street,

Frost's old home, and during the renovation discovered 33 more paintings

nailed face to the wall!

Apparently, Frank had used some of his father's paintings as wall covering.

The Masons, believing the paintings to be of some value, arranged for

the Knoedler Galleries in New York and the Child's Gallery in Boston

to display and sell some of the paintings in 1954 to collectors and

museums.

The Mason discovery and sale, however, created quite a legal problem.

The Carpenters maintained that Frank intended for them to receive all

of the Frost works in the house at 11 Pond Street. The Masons claimed

the paintings from the walls were theirs. The dispute was settled in

Essex County Probate Court in 1957. The judge ruled that the paintings

belonged to the Masons, but added that hey would have to relinquish

a carved painted wooden fish and pay the Frost estate $600 which they

had received from the sale of another painted fish. The case was appealed

to the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, but was later dropped.

Frost works were virtually unavailable on the market until 1971 when

45 Frost paintings and carvings fromt eh Carpenter collection were auctioned

by the Parke Bernet Gallery in New York City. Two were sold last year

(1979) at a Salem auction. Not surprisingly, they brought considerably

higher prices than the days when J.O.J. tried to sell them from his

wheelbarrow!

|