|

I think a sword was sheathed the other day.

I'll miss the flash and fire I've known so long.

An honored blade that proud men lay away

While it's still shining bright and straight and strong.

The sword was that of Eben Graves Weed and the poem in tribute to the

fiery, long-time editor of The Marblehead Messenger was penned by his

brother, Dan Weed. It appeared on the paper's front page three days

after Eben died on January 23, 1967.

Eben

Weed: the mischievous Marblehead farm boy who went on to famed Phillips

Andover Academy, to Yale and Harvard, served courageously overseas in

both World War I and II, and in Marblehead pursued a forty-year career

as editor and eighteen years as an official of the town he loved and

fought for so much. Eben

Weed: the mischievous Marblehead farm boy who went on to famed Phillips

Andover Academy, to Yale and Harvard, served courageously overseas in

both World War I and II, and in Marblehead pursued a forty-year career

as editor and eighteen years as an official of the town he loved and

fought for so much.

He made newspaper

publishing respectable in Marblehead.

In those years, Marblehead had no more eloquent nor fearless

spokesman than Eben Weed. He was a zealot in defending the traditons

of the 300-year

old town, yet he was visioinary enough to recognize and accept the changes

that must come with time. During his four decades of editorship, he saw

the community that once had been a fishing village and then busy center

of shoe manufacturing being transformed partially to a summer resort

and

yachting base, and then to its present status as a growing "bedroom" community.

Almost appropriately, to be witness and recorder of much of this change,

Eben was born just before the turn of the century. On February 24, 1897,

he was born on the old Harris Farm, off Village Street, to the town's

favorite postman and poet, Wallace Dana Weed and Elizabeth Graves Weed.

One of this beloved couple's five boys and two girls, Eben's local ancestry

went back to farmer Daniel Weed who settled in the town in 1750. He was,

then, should anyone challenge it, "a true Marbleheader."

Farmboy? Yes. At the Harris Farm and the Childs' Farm close by the present

General Glover Inn where Wallace Weed soon moved his family, the farming

was done by Eben Graves, the maternal uncle after whom Eben was named,

and all the boys helped. On the farm his mother became an experienced

gardener, buying seeds from as far away as England and France. Here the

boys helped again by peddling her bouquets of flowers around town.

When it came to high school, Eben went to Marblehead High while his brother,

Allan, went to Salem High. As both were skilled first-basemen and both

made their school baseball teams, it happened that more than once they

played against each other in school league games. (This sibling rivalry

carried on in later years when Eben and Allan played on opposing teams

in the North Shore Twilight League).

For reasons unrecorded, Eben's stay at Marblehead Academy on Pleasant

Street, now occupied by the American Legion, was cut short, and Father

Wallace had him transerred to Phillips Andover Academy, from which he

himself had been graduated. At Andover, Eben continued to distinguish

himself as a baseball and football player but again ran afoul of academic

authority and, for the seemingly trivial offense of sneaking out after

hours to by a sandwich, was dismissed from school.

It hardly mattered, for he had already decided to enlist in the Army and,

if possible, to do battle overseas. This he did. He signed up with the

U.S. Army Fifth Division's 20th Field Artillery and at 19 went over to

France to serve the final two years of the war against the Kaiser. The

war over, he stayed abroad and took pre-university studies in England.

Thus equiped, Eben returned to the U.S., studied another year at Milford

Academy in Connecticut and in 1921 finally arrivd in New Haven for four

undergraduate years at Yale. He worked his way through the university

as a waiter and busboy. His scholastic record at Yale was adequate enough

for him to win his degree in 1925, but again his athletic record was only

a little shor of being phenomenal. Although weighing only 148 pounds at

Yale, by 1925 he had earned 17 varsity letters in high school and college

football and baseball.

After Yale, he followed the usual graduate route to New York City and

found work in the advertising field. Two years of making the rounds of

Manhattan offices, however, made him long for the sounds and smells and

friendly people of his native town. He returned to Marblehead.

His experience in advertising had instilled in him the ambitioin to

get into printing and publishing. Upon arriving back in Marblehead

in

1927 he viewed with a calculating eye the operatioins of N.A. Linday & Co.,

job printers and publishers of The Marblehead Messenger.

The Messenger had been founded by N.A. Lindsay more than a half-centry

earlier, in 1872, but was now owned and edited by Frank L. Armstrong.

A thriving weekly, it had a circulation of 1,500 in a population of

6,785, which meant that nearly every family was a

Eben at his "retreat" in

Maine, late in his career.

subscriber. Eben could not be blamed

for hustling around among his family friends, bankers, and businessmen

to borrow enough

money to buy the company. On June 1, 1927, the name "Weed Publishing

Co."replaced the old Lindsay title on the paper's masthead, and

Eben became editor and publisher. That same masthead (the boxed space

on the editorial page) had alsways included the paper's price: "Subscription

$2.00 a year; invariably" to stand until years later when he

increased the subscription rate to $2.50.

The young editor announced on the front page what The Messenger henceforth

would indubitably stand for. He printed in large type: "We lean

to three isms and three only: We are for God, for Country and for

Marblehead". For the same front page, his brother Dan wrote

a poem memorializing the anniversary that day of the Battle of Bunker

Hill, a news article told of Charles Lindbergh's return to the States

from his historic solo flight across the Atlantic and another told

of the charge of Judge Thayer of the Supreme Judicial Court to the

jury which resulted in the conviction of Sacco and Vanzetti.

Messenger readers had not long to learn of the editorial mettle of

their new editor. In his second issue Eben, in a front page editorial,

upbraided the whole town and the Finance Committee for turning down

a town meeting article appropriating $1,000 for Fourth of July fireworks.

After reviewing Marblehead's surpassing record in the War of Independence,

he described the negative vote as "a disgrace of disinterest

and of misguided economy". Such editorials and his sometimes

angry railing at Town Meetings against various articles being proposed

gave him a reputation for bing "crotchety" but those close

to him knew this to be indeed a misnomer.

Nor did he look "crotchety". Eben was a slight man but

with the wiry build of an athlete. His face was square, the nose

rather

prominent and he had piercing blue eyes. He was no Ivy Leaguer in

looks, nor did he look like the farmer. He looked like, well, a Marbleheader.

In another early editorial Eben urged townsmen not to vote against

Presidential candidate Al Smith, Governor of New York, just because

he was a Catholic. The Messenger itself, however, was for Herbert

Hoover and it was not surprising that on November the GOP canditate

swept the strongly Republican town by 3,387 to 1,287 over Smith.

Besides Eben, two others of the Weed family were contributing to

the popularity of the weekly paper. His father, Wallace Dana Weed,

the

avuncular postman who, after studying at Andover, had gone on breifly

to Amherst College, contributed indefatigably to The Mesenger verses

of poetry about town anniversaries, legends and topical events. The

poems were of truly high literary merit and many have since been

collected

and published. Brother Dan wrote a popular column of town trivia

under the pseudonym "Josh Jokem". Articles on old Marblehead

by historians Roads, Tutt, Putnam, Robinson andothers, also made

popular

reading.

The etching for the Marblehead Messenger nameplate was done by

Childe Hassan, famed Boston artist

whose works are part of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and Washington,

D.C.'s National Gallery Of Art.

Working as a bookkeeper for the company, as she had

for Eben's predecessor, Frank Armstrong, was an attractive young graduate

of Marblehead High. Eben was more than interested in her. A courtship

began and the following year he and Dorothy Stone were married, beginning

a happy partnership which was blessed eventually with two daughters,

and in years later several grandchildren. Dorthy continued for some

time at The Mssenger, part of a staff that, under Eben, worked more

as members of a family than as company employees.

Evelyn F. Marraffa, high schoool classmate of Dorothy Stone, joined

The Messenger ostensibly as proof reader, but in the subsequent 18

years at the plant became, if needed, typsetter, folding machine,

and stencilling operator, bookkeeper and secretary. "Eben",

she recalls, "dictated much of this editorial work which was

most articulate, he just never could spell. Always, for instance,

he would spell 'waste' as 'waist' and there were so many other words

he couldn't handle."

Others in The Messenger "family" at the time included old

Marbleheaders such as Ben Lindsay, pressman and descendant of the

paper's founder; Walter Blackler, also a pressman, whose ancestor

of the same name had commanded the barge which bore General Washington

over the Delaware for the Battle of Trenton; Harold Peach, typesetter,

and over the next four decades, a procession of young and old craftsmen

who went on to greater or lesser careers.

After the panic on Wall Street in 1929 and when the spreading depression

during Hoover's administration finally and severely reached Marblehead

in the early thirties, Eben Weed experessed some of his disenchantment

with the Republicans he had supported. In a front page editorial

in

April, 1932, he  unloaded thusly: "About everything and everyone

has been subjected in the last year or two to a process of unloaded thusly: "About everything and everyone

has been subjected in the last year or two to a process of

Eben and friend on Washington Street.

debunking , a sort of deflation which must invariably

take place after the blooming of an abnormal period of prosperity.

Perhaps

the biggest flat tire of them all was ex-President Coolidge. What

a halo of bologna encircled that man during his presidential

term!

He was an economic genius, the ideal businessman in the presidential

chair, but what a flat tire today! Next to him comes President

Hoover

and Secretary of the Treasury Mellon. Today these two are not as

flat as Cal, but very little wind is left in them. President

Hoover

is an ordinary jay faced with a stupendous problem, Mellon like

a lttle boy who tried to build a skyscaper on a foundation of

sand."

Like other businessmen at the time, Eben had good cause to lament

what the recent years had done to him. "The depression nearly

ruined me," he told a friend. "I saw about $60,000 worth

of printing orders vanish overnight. I had to work like a crazy

man for ten years to put the business back on its feet." Which

was, in a way, an admission that the Roosevelt years, despite the

NRA, did help the Weed Publishing company recoup its depression

losses.

Eben had told his wife Dorothy soon after their marriage that he

would personally stay away from politics as it might interfere with

his editorial judgement on The Messenger. But his vexation with

the way school affairs were being run in town prompted him finally

to throw his hat into the ring. He decided to run for election to

the School Committee. In February 1935, he announced his candidacy,

noting that while at Yale he had for two years taken special courses

at the university's Graduate School of Eduacation. Yet , in the

same issue of The Messenger, he assailed the new salary raises announced

for Marblehead teachers, thereby defying the town's powerful school

lobby.

A friend asked Eben if he would like him to organize a "bullet"

campaign for him. "What do you mean?" Eben asked. "We'd

call upon your many friends and members of your family to cast only

one ballot for you for School committee, none for the other candidates,"

it was explained. "That sounds to me like cheating," Eben

replied, shortly. The matter was dropped. But he won the election

with 1,259 votes, going into office with Chester Parker, another

politcal newcomer. During his three-year term, Eben became watchdog

of the public treasury, a role that did not promote the adulation

of scool officials, but won him a new following among taxpayers.

When World War II broke out, Eben carried on with The Messenger

during the first of the conflict, but the stirrings of patriotism

that tradionally seem to grip Marblehead men impelled him to apply

to the U.S. Navy for the chance to serve. The Navy was hesitant

about signing on this middle-aged editor but possibly out of respect

for the town's impressive background in naval affairs, finally awarded

him a reserve officer's commission.

Following the usual officers' training, Eben was assigned to the

Atlantic Fleet's minesweeper force. By the time the Allied Forces

were ready for the invaision of Europe, Lieutenant Weed was commander

of one of the minesweepers leading the right wing to the invasioin

on D-Day. The mission was highly successful although when most of

the job was done, one of the mines Eben's craft had cleared blew

up and took away part of the ship's stern. He was able to bring

the crippled minesweeper back to Southhampon and for him the war

was virtually over.

Dorothy

Weed had kept The Messenger going full pace until Eben's return

to the editorship in May, 1945. He then printed a  touching tribute

entitiled "The Home Folks". "Now that peace is here,

" he wrote, "there will be many articles extolling the

deeds of our soldiers and sailors. To my way of thinking, something

should be touching tribute

entitiled "The Home Folks". "Now that peace is here,

" he wrote, "there will be many articles extolling the

deeds of our soldiers and sailors. To my way of thinking, something

should be

Eben sits comfortably at his desk backdropped

by his signature cause, perhaps now lost, touting the fact of Marblehead's

place in

history. Before him is the Town Report of 1946.

said for the home follks." And he told of the sacrifices, the

loneliness, losses and deprivations of local families through the

war, concluding "I hope the solidiers and sailors of Marbleheard

will not take all the glory." Coming from one nearly lost in

combat, it seemed high tribte indeed.

Again, in an August editorial that year, he wrote in anticipation

of what was to become The Marshal Plan for U.S. aid to stricken

nations. "The U.S. people, " he wrote, "have to change

their way of thinking. The idea that we are so wealthy and that

it is impossible ever to give away a substantial part of our wealth

must be discarded. We must work to free India and China and every

nation that wants to be freed. If we are honest and sincere about

this it can truly be said we are entering an age when the welfare

of man will reach heights which seemed impossible when Wilson first

dreamed the idea." Thus spoke the "crotchety" smallltown

editor from Marblehead.

But Eben was his irascible editorial self again a few weeks later

when he assailed the medical profession of Marblehead for refusing

to make house calls. "With the exception of Dr. Stanley Hopkins,"

he wrote, "the town is infested with medical specialists who

refuse to take house calls. We know they are competent in their

fields but to pry them out for an average call is a task something

like the raising of the Normandy."

By 1947 Eben was ready for another dip into politics, this time

his goal a seat on the Board of Selectmen. Running on a platform

that called for a new hospital to replace the old and obsolete Mary

Alley Hospital on Franklin Street, and for a slow down on town zoning,

he won the fifth place on the five-man board.

The new hospital issue had for long been a priority issue with Eben.

But he had his own ideas on the subject. When, years earlier, the

Goldthwaite family had offered free to the town the old Devereux

Mansion and three acres of land for a new hospital, Eben fought

the idea, claiming quite properly that he handsome wooden building

would be a firetrap for patients. The project was rejected. His

own proposal later that the Lydia Pinkham stone castle out on the

Neck, Carcssone, be obtained as a hospital site, was soudly defeated.

But he continued to campaign for a new hospital and finally the

town voted the $675,000 necessary for the present Mary Alley Hospital

that was completed in 1954. (One can imagine the editorial explosions

that would erupt were Eben Weed running The Messenger today and

heard of present plans to phase out the Mary Alley!).

Eben ran for re-election as Selectman in 1948 and, typically, at

Town Meeting the very week before the balloting, arose to propose

lowering the slaries of all town employees. "I realize,"

he told the meeting, "that what I'm saying might lose me the

election next week." It didn't. Again he placed fifth in the

race, edging out Richard Rockett who had been chairman of the board

during Eben's term the previous year.

It was probably such challenges as that of the State Board of Education

about the site for Marblehead's proposed new Junior High School

that kept Eben's combative spirits up. The state board demanded

that the site include at least seven acres of land. On The Messenger's

front page he roared: "Only a jackass or someone connnected

with the State Board of Educarion, evidently synonomous phrases,

would, looking upon Marblehead's geographic characteristics, suggest

such a thing."

And when in March, 1952, Dr. Henry Stebbins, chairman of the town

Board of Health, annnounced that a Salem man had been appointed

Marblehead's health agent his wrath was unbounded. This was just

three days before Dr. Stebbins was up for re-election. Stalking

to the home of Thomas A. Jordon, Eben insited that friend Tommy

oppose the board chairman as a write-in candidate the following

Monday. Somewhat dazedly, Jordon agreed and ran his sticker campaign

over the weekend. In the biggest upset in the town's political history,

he defeated the doctor-chairman, 2,535 votes to 1,543. Thus began

Tommy Jordan's long and varied politcal career.

Always interested in waterfront affairts and writing with some

authority becasue of his three years' naval service, Eben was an

early proponent

of the idea of a breakwater for Marblehead Harbor and in addition,

a town pier off Crocker Park. When club yachtsmen failed to rally

in support, this ignited Eben's ready ire. A front page editorial

in 1952 assailed them: "When our yachtsmen get into their whites

and loll around their clubs they do look like the cat's whiskers.

But I don't know of any group hereabouts which has acted with so

little intelligence and foresight." Nevertheless, it was the

voters as a whole who voted the breakwater idea down at Town Meeting

a few years later.

In 1953 Eben's role as watch dog for the taxpayer was recognized

by the Board of Selectmen with his appointment to the powerful town

Finance Committee, a post he held until his death fourteen years

later.

The remaining years were not easy ones. Eben appeared daily at

The Messenger office but at luchtime, on doctor's orders, retired

to

his nearby Washingotn Street home for a rest in bed. Refreshed,

he would return to the office for some afternoon work and then,

almost inevitably, and evening meeting. These years a constant

companion

was his friendly spaniel, "pepsi". The dog, too, was getting

on and it is told that Eben cancelled a winter trip to Florida to

remain by the side of "Pepsi" during the old pet's final

days.

So much for sentiment. The obverse side of Eben's nature erupted

again full force shortly afterward when a local landlord rented

the house behind the Weed place to a group of young sports who

proceeded

to keep the nights alive for the neighborhood with noisy revelry.

Complaints to the owner, Ambrose Brown, who can be named because

Eben named him in his front page editorial, were disregarded "I

planned to call Mr. Brown a rent-hog," he wrote, "but

changed it to rent-hungry. There is no similarity between Mr. Brown

and a hog, although I have never seen him down on all fours."

More balanced writing Eben reserved for literary work that he was

doing at home. The first of these was a biography he was writing

of General John Glover. He abandoned this project but did complete

his long historical novel called "Red on Black". This

told of the Abolitionist days in which appeared Marblehead characters

such as the daughters of maligned Skipper Flud Ireson (a distant

ancester of Eben) and Wiliam Lloyd Garrison, Wentworth Higginson,

John Brown and others.

That long labor completed, Eben turned more and more to his new

love, painting. Using oils and "canvasses" made from

the cardboard crates in which newsprint deliveries arrived, Eben

painted

scores of scenes, much in the primitive style of his late friend

J. O. J. Frost. Most of the scenes were of Marblehead but there

were many, too, of the camp in Maine, on Mousam Lake, near Sanford,

to which Eben and Dorothy made weekend retreats.

But the end was near. A few weeks befoe Christmas, 1966, Eben went

to the hospital for a cancer operation. He survived the operation

and was back home for the holidays. In January, 1967, he suffered

a stroke and died on the 23rd of that month.

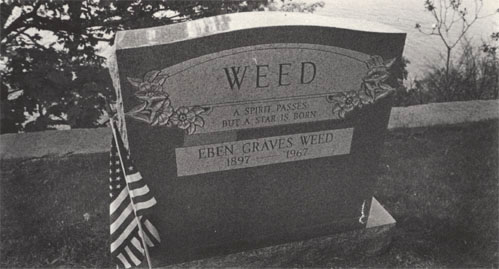

He had been no churchgoer. Private services were held at Nichols

Funeral Home, followed by cremation. The ashes lie beside a simple

stone at Waterside Cemetery, not far from the pillar marking the

graves of his early Weed ancestors.

On his gravestone:

"A Spirit Passes, But a Star is

Born."

There lies Eben Graves Weed, Editor and Patriot.

The grave of Eben Weed. In a serene corner of Waterside Cemetery

stands this simple marker.

40 years of Messengers, a legacy of tenacious reporting and editing,

along with a life of service to the Town of Marblehead have marked Eben's

place in the legend of Marblehead, undeniably.

|