|

Sometime during their fifties, men are often accused of going

through what their wives and others call "mid-life crisis".

Symptoms of this malaise are indicated by certain specific behavior

patterns, such as the purchase of a Harley/Davidson Sportster,

a Mercedes SL, or perhaps a BMW Z3 Roadster. In my case I bought

a Yanmar.

A what???

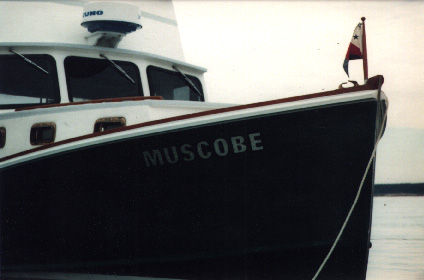

In 1986 I asked Young Brothers in Corea, Maine to build the

boat of my dreams, and the result was MUSCOBE, a 33-foot Beal's

Island hull with accommodations for my entire family. With their

experience and my imagination, we worked together to fabricate

a boat as close to perfection in design, function, safety, and

performance as I could have conceived: comfortable accommodations,

traditional salty "lobster boat" lines, and the incredible

strength required to effortlessly take on the lumps of the Gulf

of Maine with economy and speed.

Her only shortcoming was her power plant. Young Brothers recommended

a diesel engine, but at this point budget restrictions prohibited

this additional expense, and I opted for a

The proud Muscobe at rest.

275

horsepower Chrysler gasoline V8. For twelve years this engine

performed flawlessly, driving MUSCOBE at a comfortable 12-knot

cruise, with a top end of 19 knots.

But Young Brothers boats, in addition to being well built,

are designed to go FAST (not that 19 knots isn't fast). And twelve

knots simply was never really fast enough for me. A rational

person understands that lobster boats typically cruise at twelve

knots, and if you want to go faster you should buy a Sea Ray

or a Bayliner. But their trophy-filled office was evidence of

Young Brothers' many victories at the lobster boat races, and

I knew I could have it all some day.

And so, at age 56, with two of my three children in college,

when it made absolutely no sense at all (do boats ever

make sense?) I began to give in to those symptoms. I started

by searching the internet, but not at www. BMW.com. I had heard

very good things about Yanmar, so I went to their site and found

they had just introduced a new 420 horsepower turbocharged diesel

that weighed only 1300 pounds. A few weeks of serious research,

including many conversations with the local fishermen, convinced

me that this was a solid, dependable power plant. So I took the

plunge and told the boat yard to go ahead and order the engine.

My reputation for fastidious care of my boat enabled me to sell

the Chrysler engine within a few days. Soon my beloved MUSCOBE's

cockpit became a mass of confusion, with the hatches and engine

box removed. Boxes, tools, fittings, rags, wires, hoses, belts,

pumps, strainers and other paraphernalia were scattered everywhere,

making it almost impossible to move about. MUSCOBE's rudder was

removed and lay ingloriously on the floor of the shed, in order

for her propeller, shaft and cutlass bearing to be dismantled.

Where the instrument panels had been were gaping holes with wiring

harnesses hanging out. Access panels were removed and lay cluttered

about, and it looked to me as if nobody would ever be able to

make all this stuff fit back together again.

In early April the new engine arrived, shiny, gleaming, Yanmar

gray, and to me it was as beautiful and exciting as any BMW,

Mercedes, or Harley/Davidson. It was promptly unceremoniously

plunked into the empty engine compartment, where it sat on blocks

in the bilge. Then the work began in earnest. Of primary concern

was the fabrication of new braces on the beds, so that the engine

mounts could be attached and the new two-inch shaft lined up.

A special reverse gear had been ordered, with a power take-off

to run the pump for MUSCOBE's Hydro-Slave hydraulic steering

system, eliminating the old pump and belt drive. The whole thing

just fit in the existing engine compartment, with about _ inch

to spare fore and aft.

As the weather warmed, I began to make daily trips to the

boat yard to check on MUSCOBE's development. At first progress

seemed slow, and I would arrive time and again to find the engine

still hanging by the come-along, supported from a beam strung

between two stanchions. But upon more careful observation, I

noticed that each day a new support had been fabricated, or the

shock-absorbing motor mounts had been put in place, until finally

one day my new engine stood by itself on its new mounts.

One day I found a new hole and through-hull fitting, and a

new strainer for the raw water system. Big new instrument clusters

appeared in the wheelhouse and on the bridge. Hydraulic hoses,

fittings, fuel lines and the plumbing for the cooling system

were put into place. The new exhaust system was installed. Return

lines were run to the fuel tanks, and the gasoline was siphoned

out of them. When I arrived one day to find two shiny new chrome

fuel-fill deck plates with "diesel" stenciled in them,

I knew we were really making progress.

As the launch date, Saturday, May 29th approached I became apprehensive,

as there was still much left to do. My cruising partner, Al Cristofori,

who had never seen MUSCOBE out of the water, would be driving

up to Marblehead from his home in Chatham for the event. Since

Juniper Cove, where the boat is stored, dries out at low tide,

timing was important. High tide was at 11:50, so I instructed

Al he had to be here by 8 AM.

The big day finally arrived. Al got here early, so we went

out to breakfast at our favorite greasy spoon, the Driftwood,

before setting out for the boat yard. I explained that there

were a few "loose ends" to clear up, but assured him

that we would see MUSCOBE in the water by late morning.

When we walked into the shed I admired MUSCOBE's freshly buffed

green topsides, her new gold-leaf name and hail, and her gleaming

white boot stripe, shiny bottom paint and beautiful freshly-finished

teak trim. But, upon climbing the ladder into the cockpit, we

were both dismayed at what we found: still hoses, hydraulic

fittings, wires, tools, boxes, rags, wires and cables everywhere.

Access panels and plates and the hatches were still open.

"I don't think MUSCOBE's going to see the water today,"

said Al. I assured him they would have everything together in

time, but inside I had my doubts, especially when I was told

they had the wrong hydraulic steering pump.

When the one we needed was found (in Gloucester), Al and I

jumped in his car and drove up to pick it up. By the time we

returned, things were beginning to come together. Finally, at

about 2:30, MUSCOBE was moved to the water's edge and the slings

slung underneath her as the final touches of bottom paint were

applied where she had rested on her stands. "There's a little

under five feet of water left, Joel," I was advised. (The

boat draws 4-1/2 feet.) "What do you want to do?"

"Drop her in," I responded immediately. A few minutes

later her keel touched the water, and the 1999 season began.

We ran down to the float and grabbed her lines and, like the

Volga Boatmen, hauled her out of the mud as the mechanic cranked

the engine. Suddenly we heard the unmistakable deep-throated

growl of a diesel engine, and a minute later we were inching

our way out of the cove for MUSCOBE's new sea trials.

What happened next seemed at first like a nightmare. First, after

spending what I would have paid for a Mercedes, the boat didn't

go any faster than she had with the old engine! Secondly, the

engine was over-revving 800 rpms above its maximum recommended

speed. The throttle refused to stay in place by itself and had

to be held constantly. We found several hydraulic leaks, and

hydraulic fluid was all over the bilge and the back of the engine,

where it was sprayed after falling onto the spinning propeller

shaft. The sending units were apparently no good, erroneously

pegging the water temperature gauge at the extreme "hot"

position and the oil pressure at "high" when one ignition

switch was on and "low" when the bridge was turned

on. And, of course, the boat was an absolute pigpen, with footprints,

grease and oil stains everywhere. The engine box cover, which

was still standing on end in the cockpit, slid over against my

freshly-finished teak cockpit combing and scratched it in several

places. In addition to all this, the new engine was creating

some electrical "noise" which caused my depthfinder

to go crazy whenever the transmission was put into gear. I was

totally demoralized! We recorded our speed at several rpm settings,

using my new Northstar GPS plotter (good to 1/10th of a knot

and nine feet). Peter assured me that with the right propeller,

there would be a vast improvement, but now I had serious doubts

about the whole operation.

It took me two days and several scrubbings with Pamolive dish

detergent to get the boat clean enough so that water wasn't beading

up on the grease on the cockpit deck. Over the next few weeks

I got a new wheel, and any of these kinks were ironed out.

As the summer progressed, I became more familiar with MUSCOBE's

new handling characteristics including, of course, her speed.

At eleven or twelve knots you could look down at the chart or

turn to look at something out the window for a few seconds; but

at nineteen you're covering too much ground each second, and

you'd better be paying attention all the time. She answers her

helm much more quickly too. And she must look pretty good from

afar as well, because quite a few people have come up to me and

said, "Wow! We saw you flying across the bay the other day,

and that's definitely not the MUSCOBE we used to know!"

During this time Al and I conversed enthusiastically and often

about our upcoming cruise, planning and re-planning out destinations.

Our departure date was Sunday, July 25th, and I spent the day

before that provisioning MUSCOBE, loading on the dinghy, and

attending to all the little chores that precede an extended boat

trip. That night I was like a kid waiting for Santa, going to

bed early in order to make the morning come sooner, and then

not being able to sleep.

Al, who had attended a late-night wedding party, arrived early

Sunday morning for our ritualistic pre-cruise breakfast at the

Driftwood. Afterward, as we drove across the causeway to the

Corinthian Yacht Club, we looked down the harbor into a gloom

of fog so dense it seemed you could climb up into it.

Undaunted, we loaded Al's things, cranked up the radar and GPS,

and cast off at 9:15, groping our way out through the moored

boats towards Eagle Island. By the time we

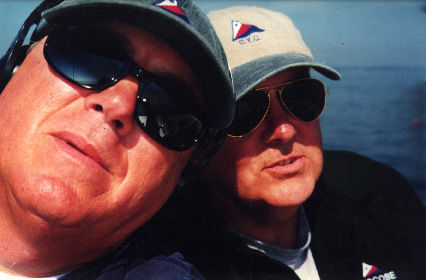

The Captain and Al in the wheelhouse.

reached

Baker's Island Light we had a good half-mile of visibility and

could increase our speed to MUSCOBE's new nineteen-knot cruise

without worrying about other traffic. The Blynman Bridge in Gloucester

kept us waiting for twenty minutes, but after that we were soon

through the Annisquam and passing the bell at the north end of

the canal, bound for Maine at last, over a smooth, gray, glossy

sea.

The sun attempted valiantly to burn but never quite made it

and though it remained calm, a big ground swell from our starboard

quarter pushed us around all day. In the early afternoon Al went

below to make sandwiches, more to relieve the boredom than to

satisfy our hunger. We droned on, and our only interruption was

the brief sighting of a pair of white sided dolphins.

Eventually the sun gave up trying altogether, and as we approached

Cape Elizabeth we were completely shut in again. Our destination

was Great Diamond Island, and I had intended to reach it by going

inside so we could view the Portland waterfront. But now we had

only about fifty yards of visibility, so I took the more direct

outer route through Hussey Sound, feeling our way along until

we finally entered Diamond Cove. It had been a workout navigating

from mark to mark in these unfamiliar waters. But the GPS and

the radar made it a breeze compared to the old days, when we

used to have to drive around in circles to make waves so the

bells would ring and the groaners would groan. I was just reaching

for the microphone to call for our docking assignment, when I

saw two attendants motioning us into the slip next to the ferry

landing. At 3:15 we tied up and shut down. The new Yanmar had

shortened our former nine hour run by one-third, and we would

have made it even sooner had it not been for the fog and the

delay at the Annisquam.

Great Diamond Island, formerly Hog Island, was an army installation,

Fort McKinley, built to protect the port of Portland in the late

1800's. It was abandoned after World War II and lay

The foggy shoreline.

deserted for many years. Recently it has been

privately developed with condominiums and private homes. The

red brick government buildings now house a restaurant, art gallery

and the General Store, among other things, and the marina is

serviced by a ferry from Portland several times a day.

After securing the boat, Al and I set out to investigate the

Diamond's Edge Restaurant and explore the vicinity. At the end

of the cove there is a peaceful fresh-water pond with lawn furniture

scattered around it, and further on is an outdoor bar and hamburger

concession. Al and I sat under some pine trees with a "corner",

enjoying the peace and serenity of the place. Little evidence

remains of the former gun emplacements and military presence

here now. The fog had thinned enough to see across to neighboring

Crow and Cow Islands, and just below us a little girl with rolled-up

jeans waded in the nearby shallows, busily looking for sea creatures

as little girls do. The view was as lovely as anywhere further

down east, and surrounded by the tranquillity and beauty of this

place it was hard to believe that the bustling city of Portland

lay just a couple of miles behind us.

There is no fuel on the island, which is just as well because

beautiful as it is, things are a bit pricey. Ice was $2.00 per

bag, and our dinner on the porch at Diamond's Edge, though delicious,

was very expensive. I suppose we must understand that there is

a price to pay for the seclusion an island offers, where everything

we use there must be ferried out to us.

Exhausted after our long run through the fog, we turned in

very early. In my sleep I was subconsciously aware of some sort

of disturbance every couple of hours. Later, we were awakened

by a bunch of young people who were having a loud party on a

boat nearby. Constantly running back and forth along the docks

and up the gangway, yelling loudly, they kept us awake off and

on, until after 1:30 AM.

During this time I became aware of the disturbance I'd sensed

earlier: it was the pulsation of the ferry's propellers as she

revved up in reverse pulling into the pier. Traveling underwater

to our hull, we could both hear and feel the vibrations. Awaking

at 6:00 the next morning I was very uneasy when I could actually

watch the big steel ferry glide into the pier, her bow towering

above MUSCOBE before it finally stopped just a few feet from

where I had been sleeping. I shuddered as I envisioned a headline

in the Portland Times: "VISITING YACHT CRUSHED IN

DIAMOND COVE MARINA WHEN FERRY'S REVERSE GEAR FAILS. CAPTAIN

DIES WHILE SLEEPING IN FO'C'S'LE."

Walking up to the heads behind the general store, we found

very nice clean shower accommodations. Afterwards we had coffee

and a leisurely breakfast in the store, served by a nice college

student who we learned lived in Louisville, Kentucky. All in

all, we found Diamond Cove an interesting and beautiful place,

well worth the visit.

By 8:30 we were under way again through dense fog. Inching

along down Hussey Sound, we listened apprehensively to many "securite"

announcements on the VHF, as vessels of all kinds departed the

busy port of Portland. Once clear of Peak's Island we had to

split the can and the nun at Green Island Passage. From there

to Cape Small and Fuller Rock our only hazard, other than lobster

buoys and other traffic, was Halfway Rock, which showed up clearly

on the radar.

By now I was beginning to chastise Al for his poor performance

regarding "The Cristofori Curse." This curse, which

we have counted on for many years, is a good one: it practically

guarantees that wherever Al Cristofori goes, good weather follows.

In all our years of cruising, irregardless of bad weather forecasts,

it has almost never failed to bless us with wonderful cruising

weather. But now we were in our second day of thick fog, and

I was beginning to lose faith. There wasn't a whole lot of scenery

along here anyway, so we didn't mind much and counted it as an

exercise in instrument navigation.

Nearing Seguin Island, we turned north and felt our way past

Pond Island light into the mighty Kennebec. As we proceeded inland,

the fog began to thin out enough for us to enjoy the scenery.

Along the way we passed a large trawler out of Bath headed in

the opposite direction, and soon we heard her give a "securite"

announcement as she disappeared into the fog at the river's mouth.

By the time we reached Bath at 11:30 it was quite warm and

sunny. We motored slowly over to the river's western bank to

observe a large yacht tied at the Maine Maritime Museum, and

then along by the ships being worked on at the Bath Iron Works.

I say "worked on" lightly: we went by four different

ships, and though each had many workers in hard-hats aboard,

we failed to see a single man actually working. All were leaning

against the rail, sitting down, or engaged in idle conversation.

The construction on the new bridge was well along, and we were

later told that it is expected to open this fall. There were

several big barges and cranes

Stern to at Bath

Town Landing.

in various places, and we watched as a tiny little

tug named PUSHER scurried back and forth pushing things into

place.

There was no room on the town landing, but as we approached

I saw space on the back, so I maneuvered MUSCOBE around and slipped

in. Fortunately there was hardly any current back there, as our

stern was now facing upriver. In any event, the tide was still

coming and it seemed to be a strong one, as the boats out on

moorings were all facing bow downriver.

After a brief walk through the business district, we entered

The Kitchen for breakfast (lunch?). There, for the second year

in a row, I was told I couldn't have my biscuits and gravy (they

only serve it on Wednesdays.) So we turned "breakfast"

into "lunch" and I had a Reuben and Al a grilled chicken

sandwich. Afterwards we walked to two places in search of fuel.

The first sold only gasoline and had no place large enough for

MUSCOBE to land, and at the other we couldn't find an attendant.

So, just forty-five minutes after our arrival, we were again

idling past PUSHER as she buzzed busily about like some nautical

bee. Slipping beneath the bridge, we turned east into the beautiful

Sasanoa River. For the first time on our trip I expressed a little

concern about not having a depthfinder. For some strange reason,

my trusty flasher-type fathometer has refused to work since the

installation of the new engine. It works fine while in neutral,

but when I put the boat in gear it goes haywire. The problem

is made worse, mysteriously, when I turn the wheel, which actuates

the hydraulic steering pump. And to completely confuse and mystify,

turning the GPS on further accentuates the problem.

It was just about flood tide as we passed easily through upper

Hell's Gate. Because of this I went straight between the spindle

and the island below the Gate, rather than go around. A little

further down we saw that the osprey's nest was still in green

daymark #21, but it seemed deserted.

Crossing Hockomock Bay we left the Sasanoa and turned north

into the Back River. The last time through here the greenhead

flies had eaten me alive and nearly caused me to run aground

in the unmarked channel, as I wildly swatted at them while navigating

up on an ebbing tide. Today, however, I was pleasantly surprised

to learn that my new Northstar 951 GPS, when zoomed in, clearly

showed the depth contours on the screen. All I had to do was

to keep the little boat between the lines. This resulted in an

easy, stress-free passage along this beautiful and little-traveled

stretch of paradise.

At 2:15 we emerged into the confluence at Wiscasset, where

the Back and Sheepscot Rivers join. We slipped over to the Eddy

Marina on the opposite side, to obtain some much-needed fuel.

I had still to learn what my new engine burns at various speeds,

and wanted very much to have this information. If I ran a tank

dry with the Chrysler, it was just a matter of switching tanks

and cranking the engine until the fuel pump got gas to the carburetor.

But when you run a diesel dry it's an entirely different matter:

you have to loosen a nut on the Racor filter and pump until fuel

flows out; then do the same on the engine fuel filter; and finally

repeat the process with the nut on the fuel high pressure pipe

on the engine. If this doesn't work, you have to loosen the injectors.

All of this can be a nightmare to do, as you drift slowly toward

the mud bank, or roll around in the waves offshore.

On our first day I had switched tanks after six hours of running.

That tank now took 51.4 gallons, which averaged 8.5 gallons per

hour. However, some of this was going slow in fog looking for

marks or traffic, so it still wasn't an accurate reading of my

burn at cruise. I "guestimated" about ten gph at our

19-knot cruise, but time would tell. All in all we took seventy

gallons and averaged 6.5 gph since leaving Marblehead.

I questioned the marina owner (whom I assumed was "Mr. Eddy")

why, on an ebbing tide, the Back River's flow had continued to

push us "up" the river. He confirmed my assumption

that the downward flow of the Sasanoa goes "up" the

Back River, thus creating the huge circular "eddy"

at Wiscasset. Thus, the Eddy Marina was named not for "Mr.

Eddy", but rather for the swirling waters that sweep past

it with each tide.

After a few drops from the edge of a passing thunderstorm,

we idled across to the Wiscasset Yacht Club. By the time we got

there the sun was out and it was quite warm. Some kids in a sailing

class were being taught how to right a sail boat after capsizing,

as we secured MUSCOBE to the far end of the dock. I completed

my entries in the log; we readied the boat for the evening, and

then Al and I headed out in different directions for a walk.

I chose to meander down the tracks that run behind the yacht

club; Al headed up into town. I hadn't gone far when I heard

the whistle of an approaching train, so I sat down to watch.

Soon an engine pulling several cars filled with passengers rolled

slowly past, horn blowing and bell clanging, as it pulled into

the Wiscasset Station. They say there's a certain romance that's

associated with trains, even these big diesels, and I felt a

bit of it myself as I watched it pass by.

These tracks lay across a stone and earthen dike that was

built to support them, with a wooden trestle in the middle, which

allows the tide to run in and out of the estuary behind it. Walking

out to the trestle, I spent a few minutes gazing down at the

rush of water flowing out with the tide. The ebb creates a large,

shallow pool inside the railroad tracks which traps many small

fish. For some time I stood watching a little blue heron stalking

his dinner. Standing quite still, he'd wait patiently until,

by a movement of his head, I could tell he'd spotted a victim.

Taking one or two slow, cautious steps he'd advance, pausing

first on one foot and then the other, until striking with lightning

speed. He never missed, and I watched him catch more fish than

it seemed his belly could possibly hold.

Beyond the trestle a wooden walkway goes out to a tiny, tree-covered

island surrounded by mud flats. There are many ancient pilings

sticking up out of the mud on the eastern side. At the shore

from where they extended were the remains of several foundations

constructed of lichen-covered granite blocks, and surrounded

by lilacs and a couple of crabapple trees. What had once gone

on here? Shipbuilding? Sailmaking? Cordage? Surely something

so near the water had to do with Wiscasset's great shipping and

trading heritage. But why would someone plant lilacs and crabapples

there?

As I stood there solemnly pondering these questions, I was

jolted back to reality when I flushed a pair of mourning doves,

who flapped up noisily just in front of me, then sailed off on

whistling wings. Walking further on, I came out of the trees

at the end of the island into a grassy area where I had to step

over many beautiful, bleached pieces of driftwood. Far across

the flats I could see a few people bent over raking for clams.

Adding to these sights and sounds was the pungent aroma of low

tide. A few steps further on, a killdeer rose and circled, crying

out its name to me repeatedly. I stood motionless for several

minutes, reflecting upon how fortunate I was to have this opportunity

to add yet another "Maine Moment" to my collection.

Then, turning back toward the trees I saw Al coming my way.

After returning briefly to MUSCOBE, we walked up to Le Garage

for dinner. Sitting on the enclosed lower deck, we missed looking

out on the wrecks of HESPER and LUTHER LITTLE, which had been

broken up and removed after the town declared them a hazard.

Wiscasset just isn't the same place without them, though in our

opinion it is still one of the most picturesque little towns

in Maine.

Next morning, Tuesday, we awoke to MORE FOG. Wandering up

into town for breakfast, we couldn't find anything open, so we

settled for coffee in the Wiscasset Hardware & General Store.

Dave Stetson, who had recently purchased the business from his

father, was just opening up. This certainly was a general

store: It held everything from models of lobster boats (equipped

with wire lobster traps now instead of wood), hardware,

plumbing and electrical supplies, dishes, and just about everything

in between. It's located just off the main street (Route 1),

next to Red's, a takeout with a reputation for some of the best

lobster rolls in Maine.

After coffee we returned to the boat to find the visibility

much improved. Buttoning the boat down (which now includes closing

the galley's through-hull fitting to prevent water geysering

up out of the sink at MUSCOBE's new cruising speed), we idled

across the eddy into the Sheepscot. The outer edges of the eddy

were clearly defined by a ring of flotsam and jetsam which the

current had spun out and left there. Most of the lobster buoys

were entangled with large masses of seaweed and sea grass, and

many were dragged just below the surface so that we had to watch

our step.

Rounding the bend and turning south toward the sea we again

encountered thick fog. Interestingly, however, it rose from the

river only to a height of four or five feet, so we could see

the trees along the shore more easily than the water (and pots)

ahead of us. At times we entered higher banks of fog, where everything

suddenly disappeared from view. Other times we could look off

at great, long, distinctly shaped patches of mist which gave

the river an eerie, haunting aspect.

There was no wind whatsoever and the river was calm, so except

where the fog prevented it, we were able to proceed at normal

cruising speed. We soon reached the southern tip of Barter's

Island, where we would turn in and down inside the Isle of Springs

(what a beautiful name!), and then into Townsend Gut. The radar

clearly showed the nun and can between which we had to pass,

but it wasn't until we were almost upon them that they loomed

out of the mist.

Once away from the river the fog seemed to disappear, though

the water surface remained mirror-smooth. We climbed up onto

the bridge to better enjoy the sun and the view. As we passed

the beacon on Cameron Point and entered Townsend Gut, we waved

down to a young boy pulling his lobster traps in a small skiff.

Al commented, "That's you, Joel, forty years ago."

A bit further in we passed a small tug headed out toward the

Sheepscot.

As we neared the Southport swing bridge, we tried to gauge

whether or not we would have to ask them to open it. As it is

supposedly the most-often-opened bridge on the east coast, we

make every effort to avoid disturbing them, though the operators

are always cheerful and friendly. Lowering our VHF and GPS antennas

we slowed and cautiously approached the bridge it was going

to be very close Coasting in neutral, ready to shift into reverse,

we slipped closer; then, lowering our heads we glided under with

barely six inches between the compass and the big green girder.

I shifted back into gear for better steerage, and was suddenly

horrified at the thought that the other side might be lower.

It wasn't.

"That was just a leetle tooo close for me," I said

to Al, and he agreed.

We had no need for fuel, but we still hadn't had breakfast, so

we pulled into the Boothbay Harbor town landing at 9:45 and walked

up to the Ebb Tide

The author on

the flying bridge.

for an omelet. By 11:00 we were on our way again,

and encountered more fog outside the harbor. The visibility was

good enough to make the going fairly easy, however, and the sun

was beginning to show itself overhead and brightened things up.

We could just make out the surf crashing on Pemaquid Point

as we passed south of it and entered Muscongus Bay. Gray, gray,

gray. More gray. Navigating in the fog is an expected part of

any cruise to Maine, and the extra challenges it brings make

it even enjoyable up to a point. But we were well into

our third day of it now, and it was becoming a bit tiring. I

wanted to see the glittering diamonds sparkling on the brilliantly-blue

sea, green-black spruces above the granite ledges of distant

islands. I wanted to catch the occasional flash of a lobsterman's

windshield on the distant horizon as he turned to haul a trap.

And I wanted to pass through those vast fields of iridescent

colored lobster buoys bobbing gaily in the sunlight. I had waited

twelve months for these rewards, and I was beginning to feel

cheated.

Soon the fog began to increase in density, but the GPS confirmed

our ded-reckoning and directed us toward Eastern Egg Rock. The

radar showed us where it lay, and the two machines guided us

easily between the daymark on the rock and the nun marking the

ledge to the north, which we barely made out as we passed unceremoniously

between them. A bit farther on we slipped through the Davis Straights

into the mass of ledges and reefs surrounding Port Clyde. Once

intimidating, these were now like old friends, and MUSCOBE was

soon clear of Mosquito Island, turning northeast toward the Muscle

Ridge Channel.

Here we encountered dense fog again. Reducing speed, we felt

our way along carefully monitoring the instruments and the chart,

while keeping a sharp eye out the window. Here we found a nun

just where it should be. There we encountered a sailboat, feeling

its own way along, where we expected to find a green daymark.

Always a busy place, Muscle Ridge was no exception today as we

worked out way up through the array of little islands, rocks

and shoals, and the host of lobster-fishing and cruising boats,

almost none of which we had the privilege of actually viewing.

Nor did we get a glimpse of little Marblehead Island as we

left Muscle Ridge, rounding Ash Island toward Owl's Head. But

the visibility did begin to improve here, and by the time we

reached Owl's Head light we could look over toward Vinalhaven

and catch a hint of the magnificent views that make West Penobscot

Bay so famous. The fog horn on Owl's Head droned out its long,

mournful bawl as we left it behind. Entering West Penobscot Bay,

we turned towards Camden and the visibility began rapidly to

increase, suddenly allowing us to enjoy the majestic views of

this most spectacular part of Maine.

Camden, as usual, was like a busy beehive. It seemed every

mooring and float were taken with boats which hailed from ports

stretching from the Maritimes to the Caribbean. Boats were rafted

three abreast along the Wayfarer Marine floats, and the docks

and landings along the town side of the harbor were jammed. Launches

and dinghies scuttled back and forth in all directions. And it

was HOT!

Our request for a mooring at the yacht club was politely denied,

as all were either occupied or reserved and float space was at

a premium. A call to the Harbormaster, however, got us some float

space at the town dock for "an hour or two," which

was all we wanted. I needed to get over to Wayfarer to see if

I could retrieve the manual to my VHF, which I had left there

several years earlier when I had gone there and spent sixty dollars

to learn that my microphone couldn't be fixed.

Al had visited Camden before but only walked the crowded streets

where the shops and restaurants are. Hiking around the harbor

to the marina (boy, was it hot!), we left the crowds behind and

came upon secluded streets with some of the magnificent homes

for which the town is noted, and he got a whole new perspective

of this beautiful place. As we walked through the bustling activity

of the boat yard, we couldn't help but be impressed by the work

they were doing. These were BIG, impressive yachts both

power and sail. Teak decks, construction and brightwork everywhere

was being worked on. Men were being hauled aloft in bosun's chairs

to the tops of HUGE masts. This is one of the few places on the

east coast that can handle the really big boats, and some of

the restorations and refits they do cost over a million dollars.

The electronics shop was deserted, and Chet, the manager,

was up a mast somewhere so we left him a note asking him to mail

my manual to me. By now I was so hot and tired I was dreading

the long walk back. I was looking at MUSCOBE, tied just a couple

hundred feet across the water from us, when one of Wayfarer's

launch drivers walked past. "Could you please take us over

to that green boat?" I asked him. (We were customers

of sorts, after all.) When he very politely agreed, we were happy

to show him our appreciation with some stuff that folded.

Back at the boat, we walked up to the Harbormaster's office,

and I told him we'd-like-to-go-up-into-town-and-spend-some-money-so-could-we-leave-the-boat-at-the-float-a-little-while-longer?

"No problem," he said. We were beginning to like the

people of Camden more than ever. Tourism is Maine's number one

industry now (not lobstering, lumber, or potatoes or blueberries),

and these people know which side their bread is buttered on.

And Maine's winters are very long. You'll never see bumper stickers

here like the one I once saw in New Hampshire ("Summer People

Some Are Not), and the only person I've ever encountered

in Maine with an attitude was somebody who had moved here recently

from Massachusetts!

We were looking for a couple of nice, cold Coronas, and I

knew just the place, so we started up the hill to a little sports

bar nearby. When Al saw they had several pool tables he got all

excited. (He is the product of a mis-spent youth.) We got our

beers and started playing eight-ball. I actually won the first

game when Al "accidentally" scratched the eight. He

toyed with me for a couple more games then, commenting something

to the effect that he'd been nice enough to me, proceeded to

run the table. Now when I think of pool players, I think of Jackie

Gleason, Paul Newman, and Al Cristofori.

After a few games we thanked the harbormaster and left Camden

for the short run down to Rockport Harbor. Rockport is the antithesis

of Camden: there are almost no shops, and the little town on

the hill seems almost deserted. The buildings of Rockport Marina

loom like big red barns at the head of the harbor. There are

several working lobster

The two voyagers

clowning around on the bridge.s

boats here,

but as Rockport Marine is one of the premier wooden boat shops

in the entire country, the harbor has many Concordias and other

wonderful wooden pleasure boats, all of which are beautifully-maintained.

We found a lovely little restored mahogany Chris/Craft lake boat

tied in a slip there, and inside the shed they were just finishing

a gorgeous 36-foot cold-molded wood down-east cruising boat.

Glass over wood on the outside, she had been finished in deep

blue Emeron and gleamed like stained glass. A 24 by 28"

four-bladed propeller hung at the end of her keel. (That's right:

she pushes 28 inches of water by on every revolution. If my calculations

are correct and I remember the gear ratio, at 2500 rpm she could

do as much as 37 miles per hour, or about 32 knots.) Inside we

could see the wooden construction, most of which was painted

white, with the wheelhouse carlins and other trim stained and

varnished brightwork. A big, gleaming white 600 horsepower Caterpillar

turbocharged diesel engine sat amidships. "How fast will

she go?" I asked. "We won't know until she goes in

the water this Saturday," was the answer. The price? "Around

four-fifty." Oh, well, as the saying goes, "If you

have to ask"

We had arrived just at closing time, but the owner very nicely

turned on the pumps so we could fill up. Because of our slower

speeds through the rivers, I was still unable to calculate an

accurate rate of fuel consumption. We got some ice, washed down,

and secured the boat in our slip. To keep the stern away from

the float, I ran an extra line from the port side as well.

Now we could relax with a "corner" before our dinner

reservation at the Sail Loft Restaurant, located adjacent to

the marina. I called home to check in (nobody there), before

we both sat down to a big plate of steamers followed by a "lobsterman's

platter," basically a fisherman's platter with half a steamed

lobster. After dinner we chatted with a nice retired couple in

a Grand Banks adjacent to us before turning in. It seems no matter

how much you think you are used to it, running in the fog is

extremely tiring. There is all the extra mental exercise involved

in constantly checking your position on the chart against the

instruments, plus the continuous peering out into the gloom where

you keep imagining you see something that's really not there.

It must tire the brain out, as I was exhausted again. The last

thing I remember was looking out the porthole at a beautiful

full moon. Could this mean no fog tomorrow?

Wednesday morning, July 28th: YES! AT LAST! An absolutely

perfect day! Cloudless blue sky; warm sun; no wind; calm, friendly

seas. After showering we walked up that agonizingly steep, knee-punishing

hill to the Corner Restaurant for sausage and eggs. Under new

ownership since our last visit, it still offers the cheerful,

friendly atmosphere and good food we remembered. You'll find

a mix of visiting yachtsmen and local people here, and everybody

including the employees seem to enjoy themselves.

After breakfast I climbed up onto the bridge and removed the

cover in order to take advantage of this beautiful weather and

the wonderful scenery we would be encountering in the Penobscot

Bays and the Fox and Deer Island Thorofares today. Al dutifully

undid the lines, removed the fenders, and held the boat away

from the float as I put her in gear.

When you do something stupid and embarrassing, it's always

nice to have nobody around to see it when it happens. In this

case, I had neglected to tell Al about the extra line I'd run

from the port cleat aft, and I myself forgot about it. So a moment

after I put the boat in gear and that big, powerful Yanmar started

pushing MUSCOBE out of the slip, we came to a sudden, screeching,

grinding halt when the line paid out! By now it was 8:00, so

of course everybody was there on the dock to watch us make a

spectacle of ourselves.

The Sampson Braid docking line had been snapped so tight around

the cleat on the float that it took us several minutes, using

a screw driver as a marlin spike, to free it. To make matters

worse, I had nearly pulled MUSCOBE's cleat out of her deck; but

that could be made right again with some bigger washers for the

nuts underneath. Al apologized profusely, but I explained that

such things are ultimately the responsibility of the captain,

and besides, I'd never even told him I had put on that line.

And so, with our tails between our legs, feeling like a couple

of yokels who have no idea of proper boat handling, we slipped

out between the moored boats of Rockport Harbor.

Perhaps it was the embarrassment, or maybe I simply didn't

feel like talking, but I spent the next twenty minutes or so

in silence. Al, on the other hand, was a real chatterbox and

didn't even seem to notice that I wasn't answering. "Boy,

it's really a beautiful day today!" (Silence) "Yes,

Al, it certainly is," he would answer himself. And so it

went, as we left a long, blue wake across West Penobscot Bay

on our way to the thorofare.

About half-way across we came upon a black Coast Guard buoy

tender; she was not under way, nor was she working on a buoy.

She just sat there as we passed, and we never did figure out

what they were doing. With the water so smooth we saw several

dolphins and a few seals. A sailboat motoring across from North

Haven toward Camden left a long "V" behind her in the

light blue mirror across which we traveled.

The Fox Islands Thorofare was as beautiful as we'd ever seen

it as we passed through in the soft morning sunlight. Before

we knew it we were leaving Goose Rocks Light behind us and making

a course for Western Mark Island on the Deer Island Thorofare.

When the visibility is good, this is an easy, well-marked run

of just a few miles, and with her new power plant MUSCOBE was

across in a matter of fifteen minutes. We slowed to reduce our

wake as we approached Billings Marine and the town of Stonington,

as a courtesy to the traffic already in the thorofare. There

are few things more annoying than to be sipping your morning

coffee in the cockpit of your sailboat, when a rude power boat

blows by you with a big wake.

We looked for seals on the many ledges through here but saw

none. Perhaps the sun was not high enough for them to enjoy it

yet, or else they were still fishing for breakfast. Just east

of the town we passed little Grog Island with its magnificent

modern, glass-faced home. I remarked for the umteenth time that

this is one of my two very favorite islands. Whoever owns it

seems to have done everything right: The house sits on the granite

ledges facing east, so they can enjoy the sunrise; they have

a sturdy little dock out front, and a couple of moorings nearby.

Behind the house is a nice wooded area, and the middle of the

little island seems to have a clearing or meadow surrounded by

the trees. What a wonderful place to be able to spend your summers!

Leaving the Deer Island Thorofare at Eastern Mark Island,

we entered Jericho Bay and made a course for the nun that marks

the entrance to the Casco Passage. This passage, and the York

Narrows just south of it, allow transit between Jericho and Blue

Hill Bays just north of Swan's Island. At high tide it looks

like a broad expanse of open water, but low water reveals numerous

nasty rocks and ledges between the two passages. It can get rather

interesting trying to navigate through here in heavy fog, because

the radar doesn't distinguish between the many navigation buoys,

the rocks, and other traffic, including the lobstermen, who scurry

around seemingly oblivious to the fog.

I say lobster men here, but it seems I'm going to have

to change my terminology. We discovered two women driving

lobster boats on this cruise. I say, "Why not? And good

for you." But what do we call you? Lobsterpersons?

Lobsterwomen? Lobsterettes? (Oops! Sorry, it's my chauvinistic

side coming through. This is going to take some getting used

to.)

Here too, you'll find wonderful Buckle Island just adjacent

to Swan's. This wonderful little place is very much worth the

effort to stop and anchor for a while in Buckle Cove. Take your

dinghy ashore. The fragrance of the conifers is like a tonic,

and the paths around the island will surprise you with scenic

vistas as good as any you can find on the entire coast. One minute

you'll be walking through a silent spruce cathedral Then suddenly

you'll amble out onto a deserted beach, with the clang of a distant

bell buoy somewhere, and muttering of a lobster boat working

in the distance.

Unfortunately, we didn't have time to stop on this particular

morning, which brings me to a point I'd like to make about cruising:

I tend to be a rather analytical person. I plan our cruises meticulously

all winter, arranging each stop at an appropriate distance, based

upon MUSCOBE's range and speed, to allow a pleasant interval

of steaming but also allowing time to explore and enjoy our destination.

This year, however, because I wasn't certain how much we'd take

advantage of our new speed capability, I was much more flexible

in our itinerary. In addition, Al had chastised me for being

too rigid in our plans: "Joel, you're in so much of a hurry

to get to Cockleberry Cove by 3 PM that you miss half the stuff

along the way. Take some time to enjoy the trip, and stop to

smell the roses. Smell Maine, Joel!"

I say this now, because I failed to take his very good advice

this particular morning. I was in a hurry to get to Corea, so

the people at Young Brothers could see MUSCOBE's new power plant.

We could stop at Buckle Cove on the way back. What happened,

however, is that we never got to see Buckle Cove, because the

weather changed our plans for the return trip. So, while we did

play it sort of loose for most of the trip, we should have stopped

to enjoy Buckle Island today. We were on vacation, so what's

the hurry?

As beautiful as it was up on the bridge, I began to get cold

as we started across Blue Hill Bay. At Bass Harbor Bar I started

to shiver under my wool CPO shirt, so I gave in and retreated

to the warmth and comfort of the wheelhouse.

There is no better part of Maine than where we were now. A

few miles behind us lay the scenic Fox Islands and Deer Island

Thorofares, Merchants Row and Isle Au Haut. To the northwest

was Eggomoggin Reach, Buck's Harbor and Castine. Just ahead lay

Mt. Desert Island and all its wonders, including Acadia National

Park and Somes Sound; and to our South lay Swan's and Long Islands,

with Frenchboro and other anchorages and vistas too numerous

to mention.

We were approaching what is generally the terminus for the

majority of cruising boats. Once past Mt. Desert, you are really

"Down East," where amenities like "yachtsmen's

showers" cease, and you often have to obtain your fuel by

getting a truck to come to the dock. Here too, one encounters

the foggiest part of the Maine coastline, and only the hardiest

and most experienced cruise here. But, as with many things in

life, those that are the most difficult to come by often turn

out to be the finest.

This morning we were headed for the place of MUSCOBE'S birth:

Young Brothers & Co., Inc. in Corea, Maine. And so, instead

of turning "left" at Long Ledge we continued eastward,

leaving the Cranberry Isles to our north, and we made a course

for Schoodic Point. Visibility was now quite good and, as it

turned out, this would be the best weather we were to have. A

few miles into Frenchman's Bay I tried calling Colby Young on

NANA MARIE, to see if we could rendezvous with him. When he answered

our call, we found that we'd passed him ten miles back, however,

so we continued on.

Passing between Schoodic Point and Schoodic Island, one comes

to a can and a nun marking the channel just north of the island.

The nun forces you to turn away from a nasty bunch of rocks,

Schoodic Ledge, but today it was nowhere to be seen. I turned

east again once we made the can and began maneuvering between

the many lobster buoys in the area. There are two dangers between

here and Corea Harbor: Big and Little Black Ledges. Big Black

ledge is a rock that always shows, but Little Black covers over

at high tide, and I've had some nervous moments hoping I was

well clear of it on the few occasions I've come through here

in dense fog. Today our visibility was good, however, and we

were easily able to pick out the surf crashing on the ledge as

we left it well to port.

Corea Harbor is beautiful in its quaint simplicity. But it

is tricky to enter if you don't have "local knowledge."

There are several rocks and ledges which cover over at high water,

and I can't ever seem to remember exactly where they are. Sure

enough, I quickly found one dead ahead of us, marked by a curl

on the surface as the swells passed over it. I knew that rock

was there; it just wasn't quite where it was supposed to be.

Moving across the cove, we kept to the east side and pulled up

to the Lobstermen's Co-op for fuel at 11:30, where we were greeted

by our old friend, Dwight.

Pulling up for fuel at the co-op is a bit different from tying

up at a marina. First, you absolutely must defer to the

fishing boats. They are working, getting their own fuel and unloading

their catch. They are always friendly and courteous, but the

last thing they want to do at the end of their day is to sit

around waiting while some yacht takes up float space. Secondly,

there are lobster cars everywhere, and in some places the floats

themselves are lobster crates. And if you're not wearing boots,

you're going to get your feet wet (as Al found out when he stepped

onto the "float" to tie us up.)

In the old days it would have taken half a day to go from

Rockport to Corea. This morning it took only 3.7 hours, during

which we burned forty gallons. This was MUSCOBE's first solid,

uninterrupted run at her new cruising speed, and it calculated

out to 10.8 gallons per hour. I had assumed 55 gallons of usable

fuel with the old engine, but with the bow raised higher with

the new engine, I decided to err on the side of caution and assume

four hours usable on each tank. With her new cruising speed of

18-20 knots, this means a range of 144 to 160 miles at that speed.

Interestingly, if we assume eight gph and 5 _ hr. on each tank,

should we slow to 15 knots, the range only increases to 165 miles.

As we finished refueling, NANA MARIE slipped in and tied up

ahead of us at the float. Colby must have really put the petal

to the metal to catch up with us this fast. We then idled over

to the Young Brothers float. It was good to be back in Corea

Harbor, where I had spent many days during MUSCOBE's construction.

The little harbor is very well protected, and the shore is mostly

granite, with piers extending out on pilings and covered with

lobster pots and buoys of many colors. It's a real working harbor

with, I'd say, thirty or forty boats. And while there are no

facilities for cruising yachts, it's charm and beauty make it

well worth going there.

Vid Young, Colby's brother, was out to lunch when we walked

up to the shop but we chatted with Harold Hammond, the manager,

and looked at Vid's new 40-footah, which was still under construction.

A new 1000 horsepower Mack V-8 diesel had just been installed.

Even with the engine and main bulkhead relatively far forward,

as is the custom with working lobster boats, the trunk cabin

was enormous! With plenty of head room and her beam of nearly

fourteen feet, I began to envision a very livable MUSCOBE V,

which would be quite comfortable down in Florida or the Bahamas

during the winters of my retirement. And there was still plenty

of room for a nice big wheelhouse and open cockpit aft. "I

have got to get me one of these," I said to Al.

And so, a new dream begins

When Vid returned, we went back to the boat for a little test

ride with the new Yanmar. Young Brothers thinks very highly of

this engine, but so far they haven't been able to convince anybody

to put one in any of their boats. Both Vid and Harold were quite

impressed with the quality of the installation, and when Vid

turned up the rpms they commented on the lack of vibration, indicating

a very good job of aligning the shaft. "This is the way

this boat was meant to go," Harold commented after taking

the wheel and bringing her up to speed. Upon returning to the

harbor, Harold expertly located the small hydraulic leak that

had been plaguing us.

I then chastised both Harold and Vid for "moving"

so many of the rocks in the cove from where I had remembered

them. They gave me instructions on how to leave (always stay

to the east side of the harbor, and favor the islands). Then,

winking, Harold handed me a set of stainless steel washers with

which to refasten the cleat we had pulled in Rockport. We said

our good-byes and went on our way, waving to the numerous fishermen

now washing down in the cove and waiting their turn at the co-op

floats.

Vid had said it was perfectly all right to go between Big

and Little Black Rocks, but they look so formidable I simply

didn't have the courage even though the chart agreed with him,

and so I went around them both. Upon returning to Schoodic Ledge

we found the missing nun. It must have been leaking, as it was

nearly submerged, with only about ten inches or so sticking out

of the water.

Rounding Schoodic Point we saw hundreds of tourists sitting

on the rocks, watching the boats go by and the surf crash on

the rocks in this part of Acadia National Park. We waved to the

crew of a very pretty little lobster cruiser headed into Winter

Harbor. This harbor is not highly recommended in "the book,"

but it looked very pleasant from where we were.

Heading northwest up Frenchmen's Bay, we put Egg Rock behind

us and soon slipped behind the breakwater on Bald Porcupine Island,

and into beautiful Bar Harbor. The town is named for the "bar"

that forms at low water between the mainland and Bar Island,

which has stranded many an unsuspecting tourist and even

some cars who stayed on the island a bit too long before

the return of the tide.

We tied up at the town landing at 2:30, where the Assistant

Harbormaster said we could spend the night for a dollar a foot.

As it was a little rocky-and-rolly, I moved the boat to the innermost

float to get as far away from all the traffic as possible.

After securing the boat, we realized how very hot it was ashore.

As is typical of Bar Harbor, it was jam-packed with people of

all sorts. The parking lot was filled with cars, RV's, and motorcycles

with plates from all

Tied

up at Bar Harbor Town Float.

over the country,

and people were walking everywhere. Beautiful yachts, windjammers,

and lobster boats sat gracefully on moorings in the harbor, and

two big, rusty steel draggers were tied to the end of the pier.

Al had never seen any of the park, nor had he been to the

top of Cadillac Mountain, so when we learned that a tour bus

went up there at 3:00, we walked up to Testa's to buy tickets

and have a Corona while we waited. As we sat at the bar the driver,

Tom, came in for a Coke and a short rest. At 2:45 I went out

to the "bus," which was one of those trolley-types,

leaving Al and Tom chatting together.

A minute or two later Al came out, strutted up into the bus

like a man with a purpose, and said, "Hi, folks! My name

is Al! Is everybody ready?" Assuming he was our driver,

everyone answered in unison, "YES!" "Okay, then,"

he said. "First I've got to collect a couple of bucks from

everybody," at which they all reached for their wallets

and took out the money.

He finally admitted that he was just another tourist, which

was good for a laugh, and soon our real driver came aboard. He

turned out to be a rather colorful third-generation resident

whose grandfather, working for the WPA, had helped construct

the carriage roads and bridges throughout the park. As such he

was able to tell us great deal about the area. As we drove up

the mountain we crossed many of those beautiful, arched granite

bridges and were treated to some spectacular views. At one point

we could see both of the new, extremely fast catamaran ferries

as they approached on their return from Yarmouth, Nova Scotia.

At the top of the mountain, in the place where the morning

sun first touches North America, we walked out onto the rocks

and were treated to the majestic view of Frenchman's Bay, looking

across Bar and the Porcupine Islands toward the Schoodic Peninsula.

Though I'd been here many times, I was still impressed by the

spectacle of it all, and wondered at the awesome forces it must

have taken to deposit all that granite surrounding us.

Back down at sea level, when we returned at 4:30, it was still

very hot. Fortunately, the walk back to the dock was all downhill,

and we were soon sitting comfortably in MUSCOBE's cockpit enjoying

a corner, as we watched all the activities going on around us

and up at the beautiful old hotel next to the town landing.

After a while Al said, "I'm starving! Let's eat."

And I agreed, so we walked into town. There were still people

everywhere and all the restaurants had waiting lines, but we

found a place where we could eat at the bar without waiting,

and we both had twin lobster dinners. Afterward, I went back

to the boat to do some housekeeping while Al walked around enjoying

the sights and sounds of town. After an ice cream, he sat and

"people-watched" before turning in.

We awoke the next morning to surprise, surprise!

more fog. There wasn't much activity going on in the harbor (apparently

those windjammer passengers like to sleep late). We never had

found where the showers were located, so we opted to postpone

both showers and breakfast. The harbor was very still as we ghosted

past the tour boats and windjammers. The sun was making a valiant

attempt to shine through, illuminating the scene in an eerie,

enchanting manner. Patches of mist stretched across the water,

through which we could just see the beautiful "cottages"

along the shore. The only movement, outside ourselves, was a

lone lobsterman working his traps inside the breakwater extending

from Bald Porcupine Island. It was extraordinarily beautiful,

and we stayed at idle speed for some time taking it all in.

Once past the breakwater, however, we were completely engulfed

and the scenery disappeared, forcing us to rely on the radar

and GPS. I was truly disappointed at this, as I wanted Al to

be able to enjoy the sight of the breath-taking granite cliffs

that make up this eastern shore of Mt. Desert Island. And the

Thrumcap, Old Whale Ledge, Old Soaker, Otter Cliff: the only

sign we had of these spectacular landmarks was what our electronic

navigation aids showed us.

Working our way southward along the shore, from buoy to buoy

and landmark to landmark, we kept hoping that it might indeed

"burn off by ten," as the saying goes. But we remained

in a total, gray void. Our only evidence of the presence of the

nearby land was a solid mass of green on the right side of the

radar screen.

As we began to turn more to the west around the southeastern

edge of the island the radar targeted the green can marking the

rock at Otter Point, and I made a course to leave it just to

starboard. Slowing down as we neared it, I reduced the range

of the radar to _ mile. Closer it came. "Keep your eyes

peeled," I told Al. It's out there at about ten o'clock.

I was beginning to suspect that it was approaching a bit faster

than it should be, when I looked out and saw our "can":

not thirty yards to starboard, a wide crest of white foam marking

the flat bow of a big barge bearing right down on us!

MUSCOBE's big rudder threw her stern around as I added power

and turned to starboard to avoid the collision. We looked up

into the eyes of a young man staring down at us from inside the

pilot house as the barge passed by us and quickly disappeared

into the gloom. Fortunately, everybody did exactly as prescribed

by the rules of the road: he maintained course and speed and

we got out of his way, so a potential calamity was avoided. For

a split second I had considered turning to port to avoid him,

but something in the dark recesses of my memory told me that

the burdened vessel should always turn to starboard in

these situations, and so before my brain could calculate or reason

which direction was most advantageous, instinct had me turning

the wheel to the right.

Now, as I have said, a little fog on a cruise is all right. Even

two or three days. But this incident made me realize just how

fed up I was with it all by now. This was our fifth

The author piloting through a fog.

day

in paradise, and we'd hardly had a glimpse of any of it! "I've

had it," I told Al. "We're going to Northeast Harbor

and sit this one out."

A bit further on the radar showed several targets coming out

of Seal Harbor, as some boats made their way out. "Let's

go in and look around," I said. "We can check this

out as a potential future layover." By now the sun was trying

to burn through again. As we cautiously inched our way in toward

the can at the mouth of the harbor I was understandably

gun-shy at this point we could just make out those other

boats through the murk as they passed by us to starboard.

Seal Harbor is a delightful little cove, with a few working

fishing boats and a good selection of the beautiful "lobster

cruisers" so plentiful in this area. The Rockerfeller family

pier and boathouse are on one side of the harbor, and the yacht

club and town pier are at the opposite side. As I understand

it, the little yacht club is very nice, and there's a takeout

restaurant nearby. Another eating place is located up the road

a half mile or so. Aside from its southerly exposure, this seems

like a nice place to visit, though it's probably overshadowed

by nearby Northeast and Southwest Harbors.

After a circle around the cove, we plunged back into the fog

and worked our way the remaining distance to Northeast Harbor.

Tuning in the harbormaster on the VHF, we listened as several

people were told there were no slips available for tomorrow

Friday night. However, when we called and requested a one-night

stay, we were pleased to learn that they had one available for

the night. As I have already said in reference to Camden, I must

reiterate how accommodating these people are to transient yachts.

In all the years I've been listening and talking with the harbormaster

here in Northeast Harbor one of the busiest places on the

coast of Maine they have always been pleasant and

courteous, bending over backwards to please everybody and make

them feel welcome.

At 9:30 (was it only an hour and a half ago that we left Bar

Harbor?) we were directed to a slip between MAUREEN III, a Hinkley

Talaria, and PAINTED LADY, the beautiful red yawl we had been

alongside last year. Nobody was aboard either boat, but MUSCOBE

looked pretty good nestled in between what must easily be more

than a million dollars worth of yachting hardware.

Inside the harbor it was warm with hardly a trace of fog,

but from the distant horns and whistles we knew it must still

be thick outside. We settled up at the harbormaster's office,

chatting for a while with these very pleasant people. The harbormaster

himself had retired from the Coast Guard some time ago. He had

operated an ice breaker in the Kennebec River, among other places,

and had some interesting yarns to spin about his experiences.

We then walked up the hill into town to The Colonel's Deli,

which the locals had highly recommended for breakfast (they were

right). We had a couple of delicious omelets and homemade toast,

washed down with orange juice and coffee.

By now Al decided we had been at sea too long and needed some

exercise, so we went off to find a place where we could rent

bikes. I was secretly hoping he wouldn't find one, but he soon

discovered one up the street. A few minutes later we were pedaling

off toward Somes Sound on a couple of mountain bikes, armed with

a makeshift map of the area, including Acadia National Park.

It was now very hot, and as we followed Sargent Road along the

eastern shore of the sound, I was tempted several times to stop

and jump into the crystal-clear inviting water. After a while

I started to get worn out and, concentrating on the stretch of

road just in front of me, I inadvertently passed Al who had turned

off the road to chat with some of the locals. When I reached

the end of the sound I pulled over under a tree for some shade

and

Mounted up at

Northeast Harbor Bike Shop.

a rest, while I decided whether to continue on

or turn back (Al had the map). Soon, however, I heard a yell

and looked back to find him huffing and puffing his way up the

hill to where I was sitting.

We were looking for the Giant Slide, a trail that leads through

the park and eventually back toward town. Al had obtained two

sets of directions on how to find it, but at this point we were

more than a little lost. I grabbed the map and insisted that

it was "just down the road to the left" while he argued

that we could pick it up if we went right until we found a rest

area and parking lot leading into the park. Fortunately, at this

point a municipal worker stopped and showed us the way (left).

Without my reading glasses I was unable to see how close together

on the map the contour lines were at the Giant Slide. We were

soon pushing our bikes up a steep, winding path through the woods,

bouncing them over roots, rocks, and logs. I was quickly exhausted,

both from the exertion and the heat, but whenever I stopped to

rest the mosquitoes would find me. Al had fortuitously bought

us each a little bottle of spring water before leaving, for which

I was now eternally grateful. But I cursed him anyway for his

bike ride idea, for dragging me way out here in the boonies,

and for putting me through the agony of climbing this goddamn

mountain we now seemed to be on.

Undaunted, he'd just smile at me and say, "Come on, buddy!

We're almost there" And soon, sure enough, we eventually

came out of the woods onto a bike path paved with linpack and

lined with those big granite boulders that are everywhere throughout

the park. The road inclined slightly upward and

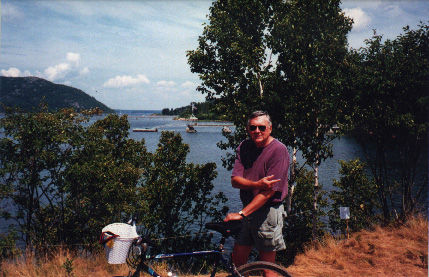

On the trail with Somes Sound in the

background.

disappeared around a bend into

the trees. "Come on, buddy!" he said again enthusiastically.

"The hill probably ends right around the corner, and we

can coast all the way back into town."

And so we pedaled up the hill and around the bend. And up

another hill and around another bend. And yet another, and another,

and another At one point I passed him when he got off to push

his bike, and I struggled on until I saw a rock in the shape

of a recliner upon which I could lie down. At least we were high

enough now where there was a slight breeze which kept the mosquitoes

at bay. I took another swig of my now precious water and collapsed,

gasping, onto the rock where Al caught up with me a few minutes

later. As he pedaled past me I looked beyond him, up still another

long grade, and gasped, "Al, when we get back to the MUSCOBE,

I'm going to find out once and for all if I can BEAT YOU UP!"

With

great reluctance, I climbed back onto my bike and followed him

up the hill. After what seemed like hours, we finally reached

what appeared to be the top. Al raced on recklessly ahead of

me, while I touched the With

great reluctance, I climbed back onto my bike and followed him

up the hill. After what seemed like hours, we finally reached

what appeared to be the top. Al raced on recklessly ahead of

me, while I touched the

Sealegs are different from real legs.

brakes,

unsure of my traction in the loose linpack. A minute or so later

I caught up with him where he had stopped at a bend in the road

and taken out his camera.

"Joel, stop!" he yelled. "I want to take a

picture." Without even slowing down, I muttered several

expletives at him and roared past. Gradually the coolness of

the breeze on my face and body refreshed me, and the agony from

the miles of pumping began to ease out of my legs and back.

The trail ended at one of the stone gate houses on the park

border. Route 193 ran straight into town from there, but it had

no room for bicycles and was very busy, so we picked another,

quieter trail. Unfortunately, this dead-ended in a little cemetery,

so we were forced to backtrack and take our chances on the highway,

grateful at least, that it was all down hill the rest of the

way.

A short time later, two utterly exhausted, sweaty, travelers

turned their bikes back in at the Northeast Harbor Bike Shop.

"Joel," gasped Al as he settled our account. "Go

next door and get me water. Right now!"

As we walked back down to the boat and approached the field

and tennis courts near the marina, Al told me, "You know,

you did pretty well today for an old goat who's so out of shape."

That was all I needed: Looking across the 100-or-so yards

of the grassy field I said to him, "Oh, yeah? Well this

old out-of-shape goat can beat your butt to the other side of

that field." Al, who is a ferocious competitor, needed no

further urging and instantly we were off, running full-tilt.

Half-way across we were neck-and-neck, when we must have realized

just how silly we must have looked: two fat old men, doing a

very poor simulation of a sprint, grunting and groaning their

way over the grass toward the marina. At this point we both started

laughing at ourselves, and by the time we got to the other side

we were making so much noise that a dog started chasing us, which

made us laugh all the harder, until I just fell down in hysterics,

with Al standing over me clutching at his sides.

Old men or no, we were pretty proud of ourselves "If

you didn't have a heart attack today, buddy," Al told me,

"you're never going to have one." Then he added,

under his breath, "You'll probably die of a stroke, from

stress, though."

We were now very ready for those famous Northeast Harbor

"4-minute showers." I say "4-minute" because

here in the "Yachtsmen's Building" they have machines

in the showers into which you insert four quarters, for a minute

of water each. Now, I like to take long showers, but I also don't

like to throw my money away. So I was all done shampooing, washing,

and rinsing off in about three minutes, with a minute to spare

to stand under the cold water when I finished. Al put in another

set of quarters, just so he could stand under the cool water

an extra four minutes.

Afterwards, walking back to the boat, I was reminded of my

one pet-peeve about this terrific marina: they allow all the

boats to tie up in their slips bow-in. This is fine, but many

of them have pulpits, on which are mounted large plow anchors,

and these extend out into the walkway. Several times in the past

I had turned to look at who I was with, only to be nearly bonked

in the head by one of these. This could be especially hazardous

to some poor soul coming back from town late at night with a

couple of "corners" under his belt. I mentioned this

to the harbormaster and suggested it might be a good idea to

require boats with pulpits to tie up stern-to, but I don't think

it went over well. I also reported the waterlogged nun at Schoodic

Ledge to him, so he could notify the Coast Guard.

Refreshed after our terrific (but brief) showers, we enjoyed

a "corner" in MUSCOBE's cockpit. WE listened to some

Sarah Brightman for a while, and then I told Al I had a special

treat for him. Digging down into my box of cassette tapes, I

pulled out a copy of a Thanksgiving day radio show that had been

recorded at Marblehead's local station, WESX, in 1953. Featured

on this program were my Dad (age 37; I was ten), his friend Tom

Hussey, the voice of the Red Sox in those days and, accompanying

them on the piano, Edith Mehaffey. I grew up in a home filled

with music: classical records and the voices of both my parents

and their many friends. This wasn't just singing old songs around

the piano. Many of these people, including my mother and father,

were trained professionals. I took all this for granted until

I was much older, and now with Dad gone I hadn't heard his voice

or listened to this tape for many years. The quality of the recording

isn't up to par with today's technology, but there was no mistaking

the tremendous talent in these voices. Tom's rich bass immediately

brought back a flood of memories of growing up in the 1950's.

Then my father's tenor rang out, crystal clear, with the words

to The Old Gray Mare, a song I'd heard him sing a thousand

times, and my vision blurred with tears, which ran unashamedly

down my face.

I had never before played that tape for anyone outside my

family. Al, the quintessential Italian, immediately sensed this

and appreciated the gesture. Soon we were both all choked up,

as we shared stories about our Dads. People nearby probably wondered

about the music coming from MUSCOBE's cockpit, and the intense