|

Each

summer tourists come to Marblehead to enjoy fresh seafood, swim

in the chilly Atlantic, and relax in the sun by the shore. But,

in the early 1800's, some of these pleasure-seeking travelers

got a little more than they bargained for. Each

summer tourists come to Marblehead to enjoy fresh seafood, swim

in the chilly Atlantic, and relax in the sun by the shore. But,

in the early 1800's, some of these pleasure-seeking travelers

got a little more than they bargained for.

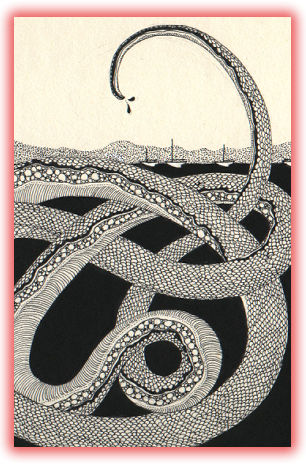

Sea serpents have been a part of all of human history all over

the known world. The Scandinavians, Asians, and even the skeptical

British, well-known for their conservatism and reserve, have

had reports, over and over, including eye-witness testimony,

of the existence of such creatures. Sea serpents, and the myth

surrounding them, have terrified and fascinated people everywhere

since the beginning of time. Some historians have wondered: with

all of the enchanting magnetism of these stories, told in every

language, can there be, after all, any truth to them? Perhaps

the sophisticated scorn for mythologies current among today's

intellectuals has caused these stories to hide in the shadows

of modern histories, but they are still there, just as they were

in their heyday of the early 1800's.

In the age when whalers and fishermen went to sea with the same

sense of adventure and of going off into the unknown as our space

faring explorers do today, perhaps this stories of serpents and

monsters were easier to believe. The Loch Ness Monster legend

is well-known, but some of these stories are much, much closer

to home than Scotland, as a few remaining Marbleheaders, still

alive today, can well attest from Grandfathers' stories and memories.

It was during those early years when Captain John Peach had just

passed on and "Flud" Ireson was being tarred and feathered,

when the names of Marblehead's Streets were just being changed

from Ye Queen' Highway to Washington Street, and from King Street

to State Street, that a new resident took its place out in the

harbor. Not the last, nor the first, but certainly the most famous

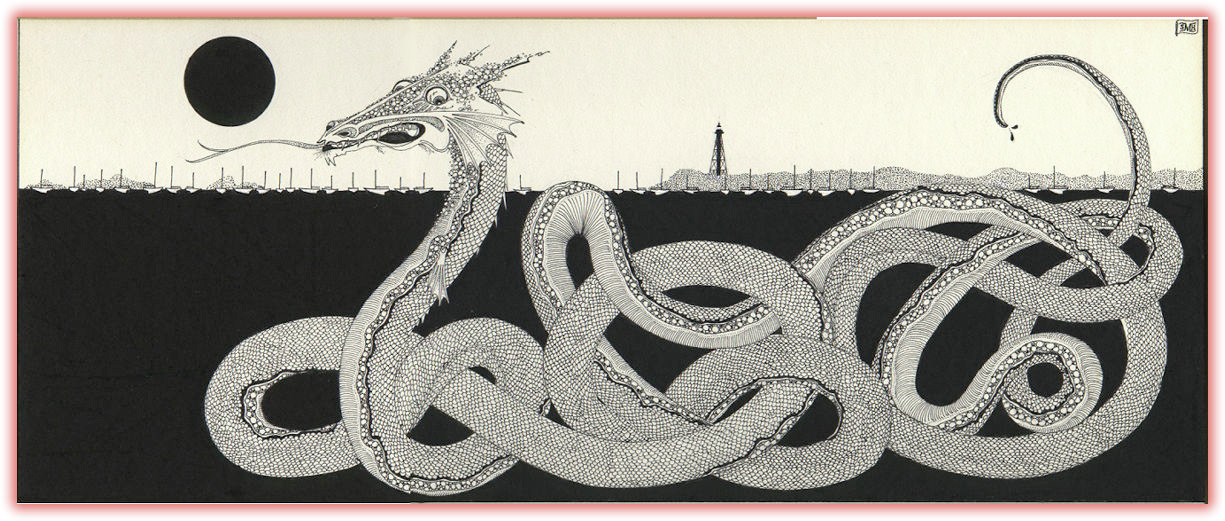

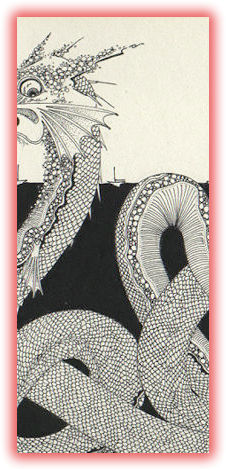

sea serpent in our history, His Snakeship, as he was called,

the great sea serpent of Marblehead spent a memorable summer

here. The visibility, the fame which spread far and wide, and

the persistent presence here challenged all doubters, and still

does.

The first documented entry of a sea serpent in this area was

made by the naturalist John Josselyn, when he reported a "huge

snake" curled around the rocks of Cape Ann in 1639. For

more than a century after that there were constant reports of

such a creature and even when told by reputable and respected

people, they were scoffed at and ignored, perhaps even as you

are now doing.

In 1779, the highly-esteemed Commodore Edward Preble told of

his encounter with a serpent, which he reported to be over 150

feet long and a big around as a barrel. Even Daniel Webster witnessed

the appearance of a sea monster somewhere between Monomet and

Plymouth. But all of this was just prologue to the summer of

1817.

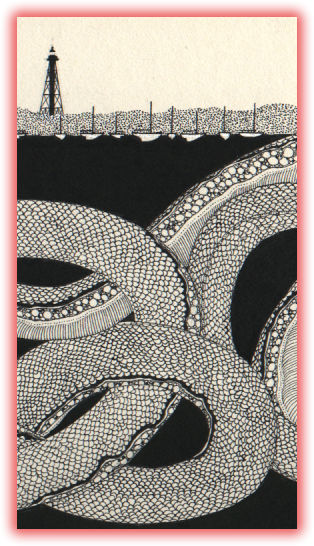

Apparently the rich feeding grounds and cool water of Cape Ann

and Massachusetts Bay attracted His Snakeship here for the months

of the summer, and for ten more summers after that. He was seen

by so many people of impeccable credibility and solid reputations

that their observations cannot be rationalized away. Overactive

imaginations, group hallucinations, or what was known in those

days as "a touch of the grape," may explain some things,

but they cannot hope to touch the legend of His Snakeship. Sightings

by groups of people up to over 200, often at extremely close

range have locked solidly down the fact of Marblehead's famous

sea serpent. Loch Ness Monster mover over, here comes a distant

cousin who was not illusive or impossible to find. This guy was

impossible to miss as he romped in the harbor like a seal. There

were times when no one was sure what the animal

was, but everyone was sure that is was. And, in Marblehead,

where everyone always questions everything as a strict matter

of tradition, that is saying something.

On August 2, 1817, two women watched as a sea serpent swam casually

into Cape Ann Harbor north of Gloucester roads, and nonchalantly

swam back out again, out to sea. Several fisherman confirmed

this report, and later in the week the creature was spotted again

from the shore cavorting near Ten Pound Island. On August 12

and 13, shipmaster watched as the serpent played in the water.

The written report read:

I, Solomon Allen III, of Gloucester in the county of Essex,

shipmaster, depose and say: that I have seen a strange marine

animal, that I believe to be a serpent, in the harbor in Gloucester.

I should judge him to be between eighty and ninety feet in length

and about the size of a half barrel, apparently heavy joints

from his head to his tail. ...His head formed something like

the head of a rattlesnake, but nearly as large as the skull of

a horse. When he moved on the surface of the water, his motion

was slow, at time playing around in circles, and sometimes moving

nearly straight forward. When he disappeared, he sand apparently

straight down. ...I saw him on the 12th, 13th, and 14th of August

A.D. 1817.

The next day 20 or 30 people gathered to watch the playful monster.

It seemed as though the serpent had settled in for the summer

season. He could be spotted each day acting the typical tourist

and enjoying the sun, water and seafood. But, while he did mind

his own business disturbing no one but the herring population,

the brave citizens of the area reacted to this creature in an

unfortunately typical fashion. A hue and cry was raised, and

four boats full of armed men took after the serpent. One of the

stalwarts shot the creature in the head at pointblank range.

Apparently unhurt and unperturbed by this inhospitable action,

the animal simply swam under their boats, surfaced some distance

away, and continued to amuse himself for the next several days

by investigating the shoreline.

For the next week he was seen every day, and one brave soul came

within an oar's length of him. Despite being shot in the head,

beaten with oars, and followed incessantly by people in boats,

His Snakeship continued his leisurely vacation while the Linnean

Society of New England hurriedly convened around conference tables

to discuss his nature, origins and ultimate fate.

The Linnean Society, inspired by the systemic scientific methods

of the Swedish botanist Linne, formed a select committee of three

carefully-chosen members: a judge, a doctor, and a naturalist.

The committee chose the equally reputable Honorable Lonson Nash,

himself a witness to the serpent's antics, to take sworn affidavits

from the other witnesses. The committee then took under consideration

this lengthy and detailed testimony, comments from Nash, and

previous reports concerning the serpent.

From all accounts the unwelcome visitor did indeed look like

a huge snake, though his movements made it obvious that he wasn't

an ordinary snake to be sure. He had smooth dark brown, blue

or black skin with a whitish underside. Although there were reports

of the creature being up to 125 feet long, he was generally thought

to be 65 to 75 feet long. The head, held about a foot above the

surface, resembled that of a snake or a turtle, was about the

size of that of a horse, and there was a series of humps or bunches

along his back when he surfaced. The beast could move at quite

a clip, with a top speed estimated at 40 or 70 knots.

Hundreds of people saw the creature in various locations, under

different conditions, but there were no great discrepancies in

their descriptions of his appearance. Yet the Linnean Society,

disregarding obvious physical evidence to the contrary, decreed

that His Snakeship was indeed just that -- a snake, a land reptile.

In the face of this invalid conclusion, the Society lost considerable

credibility, and badly confused the record of the sea serpent,through

their report.

Nevertheless it was impossible to ignore the creature swimming

around the bay, and a reward of $5,000 for the serpent -- dead

or alive -- was posted. Whalers, sailors, and adventurers set

out in hot and noisy pursuit. At this point, either annoyed or

bored by the uproar, the monster moved to more quiet waters.

One day he was seen asleep on the surface out to sea, and for

the next  several days fishermen

encountered him miles out. By the first week of October, he'd

wandered as far as Long Island Sound. several days fishermen

encountered him miles out. By the first week of October, he'd

wandered as far as Long Island Sound.

Scientific interest in the creature continued. Of all the international

sightings of marine animals, the Massachusetts Snake was widely

accepted as the only true sea serpent. He was given the generic

name of Megophia monstrous, or big snake.

In the summer of 1818, the serpent reappeared to up summer residence

once again. He was again seen by large groups of people, and

several times, whalers came within a few yards of him to heave

harpoons. Still, the creature kept his amiable disposition, though

he did become a bit more wary.

Captain Richard Rich, a whaler, had managed to harpoon the creature

once, but the serpent shook off the weapon and escaped. Determined

to capture the animal, Captain Rich and his crew spent days hunting

for the serpent . Within a week, The Boston Advertiser

proclaimed the success of the expedition; Rich had captured the

sea-serpent! But instead of the 100-foot monster which they had

expected to find at Boston Wharf, they found a rather average-sized

tunny. Rather than admit their failure to capture the beast,

Rich and his crew had apparently played a practical joke on the

journalists.

Skeptics now felt vindicated in their opinions that there was

no such thing as a sea serpent. This slapstick conclusion to

the episode, added to the confused verdict of the Linnean Society,

seemed to discredit His Snakeship further.

However, one tuna fish wasn't about to make two summers of sightings

just disappear. The Boston Weekly Messenger noted about

the Rich case:

The fish taken by Captain Rich ... is the Tunny, or Horse

Mackerel. ... The inquiry naturally arises, can this fish, or

any number of them, be the monster so often described as a sea

serpent? We answer decidedly, no. The existence of some remarkable

animal in our waters last summer, particularly near Cape Ann,

was proved by the most satisfactory testimony, and the appearances

which he presented are not in any degree to be accounted for

by supposing any number of the fish now taken. The descriptions

which we have had this season of the  serpent

have been less consistent and satisfactory, and undoubtedly often

exaggerated. But neither these exaggerated descriptions nor the

error of persons who by mistake have been pursuing what had nothing

of the remarkable ought to lead us to suspect all former testimony. serpent

have been less consistent and satisfactory, and undoubtedly often

exaggerated. But neither these exaggerated descriptions nor the

error of persons who by mistake have been pursuing what had nothing

of the remarkable ought to lead us to suspect all former testimony.

Another editorial gave Rich credit for good intentions and

added:

But while due attention is paid to his statement, the mass

of evidence presented last year ought not to be overlooked. The

appearances described by most of the observers who have given

their testimony under oath, differ materially from those by which

Capt. Rich was deluded... Gentlemen... who had the best opportunities

of observing in the summer of 1817 and several of those whose

statements were published by the Linnean Society are still confident

that they could not have been mistaken.

Repeating quotes from reputable witnesses, the editors added,

"We leave it to our readers to conclude whether the above

testimony made deliberately on oath by men of respectability

is utterly false and groundless. If so, we should be glad to

know on what grounds human testimony is to be credited."

Meanwhile, back in the waters of Marblehead, the sea serpent

continued to spend his summers in the area. By now he was a familiar

sight and a common occurrence, even though he kept startling

people in their boats and on their moorings. In August, 1819,

the serpent was sighted off the Nahant coast, and Gershom Bradford,

A noted maritime historian and sailor reported that:

Hundreds of people congregated on the beach for a look at

a strange monster. It deserves particular attention for it was

brought under the scrutiny of Samuel Cabot, James Prince, and

James Magee, names that carried power and confidence in Boston

at that period. Their descriptions are of an animal little different

from that of the Gloucester visitor.

Nahant now evidenced some special attraction for His Snakeship,

since he appeared there every day in the summer of 1822. He wasn't

spotted around Massachusetts Bay in the summer of 1825, but he

did return in 1826.

By this time the reports of the creature were so frequent and

so uniform as to be almost monotonous.

The eminent Professor Benjamin Silliman wrote: "To us it

seems a matter of surprise that any person who has examined the

testimony can doubt the evidence of the sea serpent." Some

of the stories were undoubtedly embroidered or overblown, but

there was little doubt that some sort of creature existed. One

skeptical poet wrote:

But, go not to Nahant lest men should swear

You are a great deal bigger than you are.

In the next years, the serpent kept a low profile and wasn't

seen in the area between 1827 and 1832. But in 1833, 1834, and

1835 he was back in his old haunts, traveling as for north as

Maine and Canada. Reports now mentioned a mane, more noticeable

eyes, and, in several cases, rings near the neck.

Perhaps the area had lost its charm for the creature, as his

visits became more infrequent. He was seen in 1848, 1875, 1877

and 1879, but they were for the most part individual sightings,

and he no longer spent the entire summer lolling in the area.

Sea serpents now seem to have joined the mythical pantheon of

maritime lore. But just because he is no longer sighted, His

Snakeship may still be out there and may well appear again, just

when we least expect it. As the editor of a Boston newspaper

described the opinion of the editor of the New York Gazette:

"He gravely affects to doubt the existence of the sea monster

off our coast. Perhaps he has yet to learn that it is as much

the part of folly to doubt in the face of abundant and unquestionable

evidence as it is to listen with credulity to vague and improbable

rumors."

He is that curling serpent

That in ocean is

Sea fright he is,

And shadow under the earth.

It is never there

And already vanishing.

-- William Stanley Merwin

"Before That" (1963)

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - -

Dan McDougall, for many years, led, with his brother, Mike, one

of the most successful advertising agencies North Of Boston.

He is a Salem native who has always loved the sea, sailing, and

maritime legends.

Meredith Reed, assisted in the writing and editing of the original

version of this story which appeared in Marblehead Magazine in

the Summer of 1981 (Volume II, Number 2).

|