|

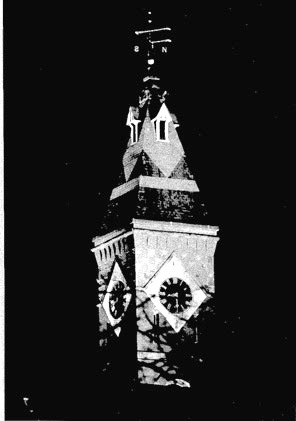

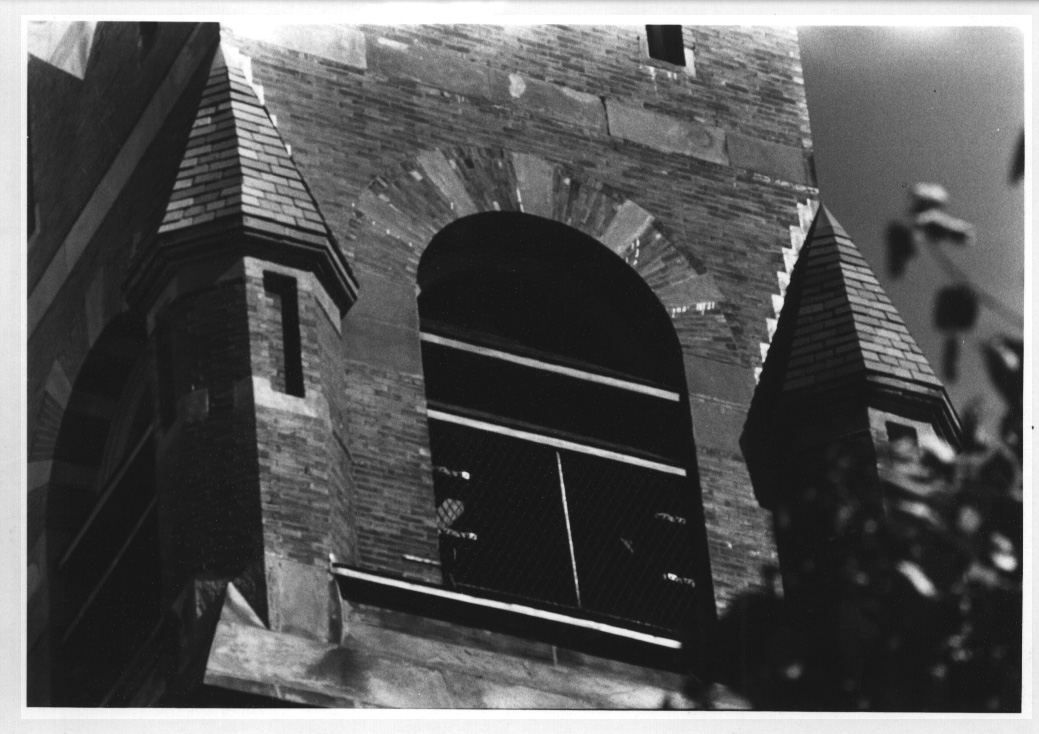

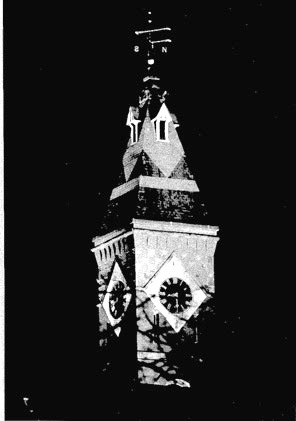

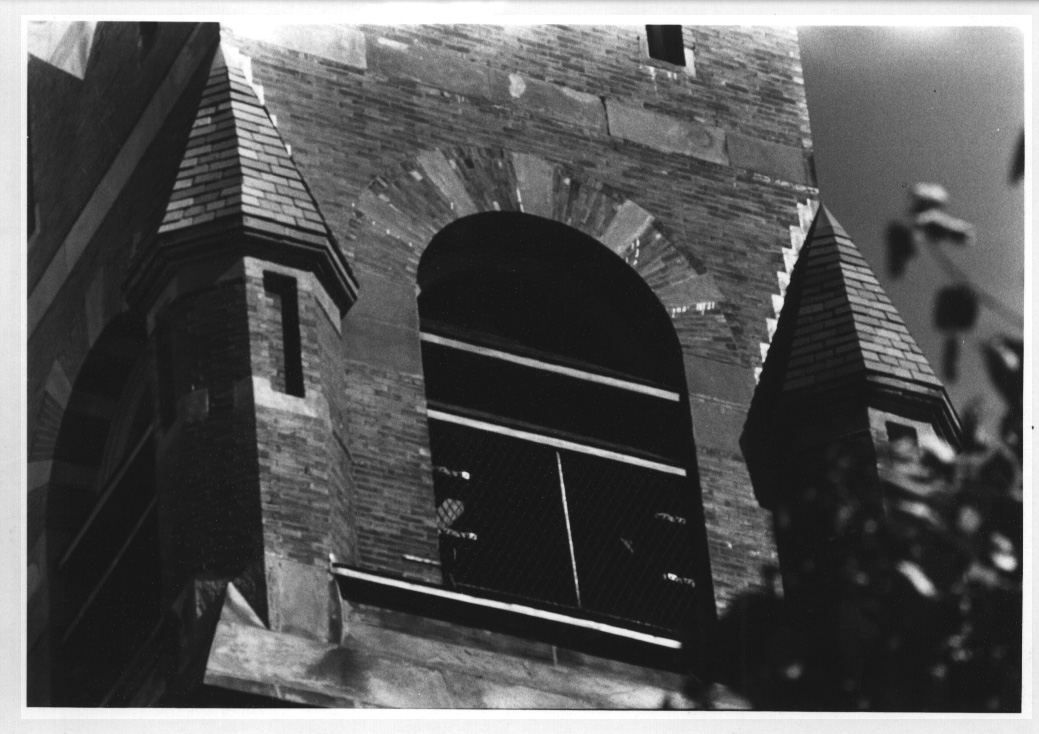

At the penultimate way station on the stairway to the top of the tower, you will notice the clock ticking beautifully, perfectly. Having climbed over the dusty boards, under the clock mechanism, through the ancient rafters to this point, the amber darkness and the arrestingly historic feeling fills the tower. At the penultimate way station on the stairway to the top of the tower, you will notice the clock ticking beautifully, perfectly. Having climbed over the dusty boards, under the clock mechanism, through the ancient rafters to this point, the amber darkness and the arrestingly historic feeling fills the tower.

Adjusting my stance to assume a better position for a closeup

photograph of the delicate workings of the fragile timepiece,

I was slightly off balance and touched the mechanism by mistake.

The entire clock seemed to hestitate for a split second. There

was a small noise inside, almost like a mechanical protest over

my disruption of monotony over all these years. And, then, the

clock was smooth and synchronous again. "I've altered time," I

thought. But, if so, I did it gently, slightly, not the way Marbleheaders

usually do.

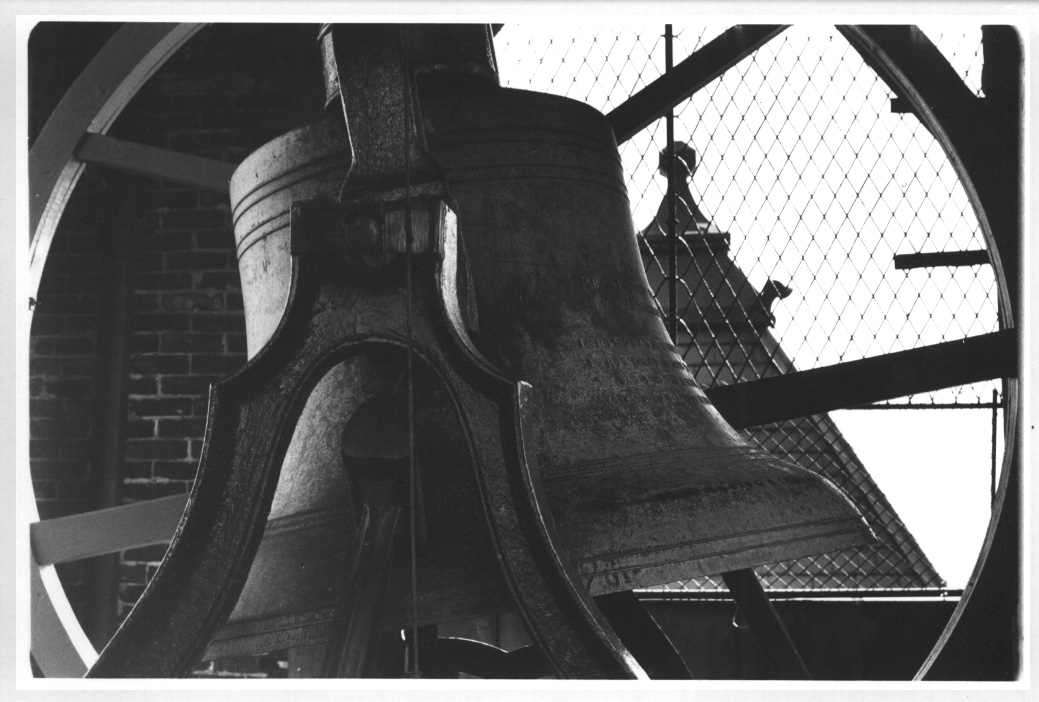

When the bell of Abbot Hall rings, it is felt as much as heard.

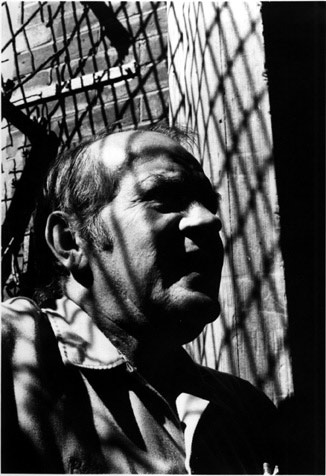

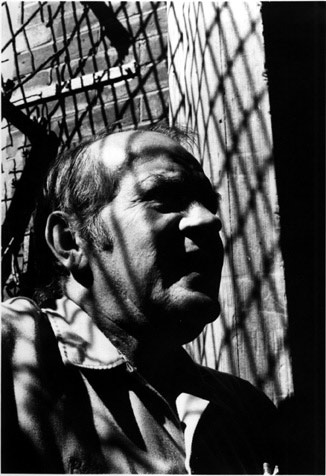

The clockmaster that day, Bert Thibault, was  covering

his ears, but the 72 noontime peals penetrated deeply into mine,

and beyond my ears into my consciousness. The noise was so loud,

everything seemed silent and muted in its aftermath. Bert told

me of the inscription that mandates the ringing and when. As

he read it to me, his voice was hard to hear as a sequel to the

bell itself. covering

his ears, but the 72 noontime peals penetrated deeply into mine,

and beyond my ears into my consciousness. The noise was so loud,

everything seemed silent and muted in its aftermath. Bert told

me of the inscription that mandates the ringing and when. As

he read it to me, his voice was hard to hear as a sequel to the

bell itself.

"I ring at twelve the joyful rest of noon;

I ring at nine to slumber sweet of night;

I call freemen with my loudest tones,

'Come all ye men and vote the noblest right.'"

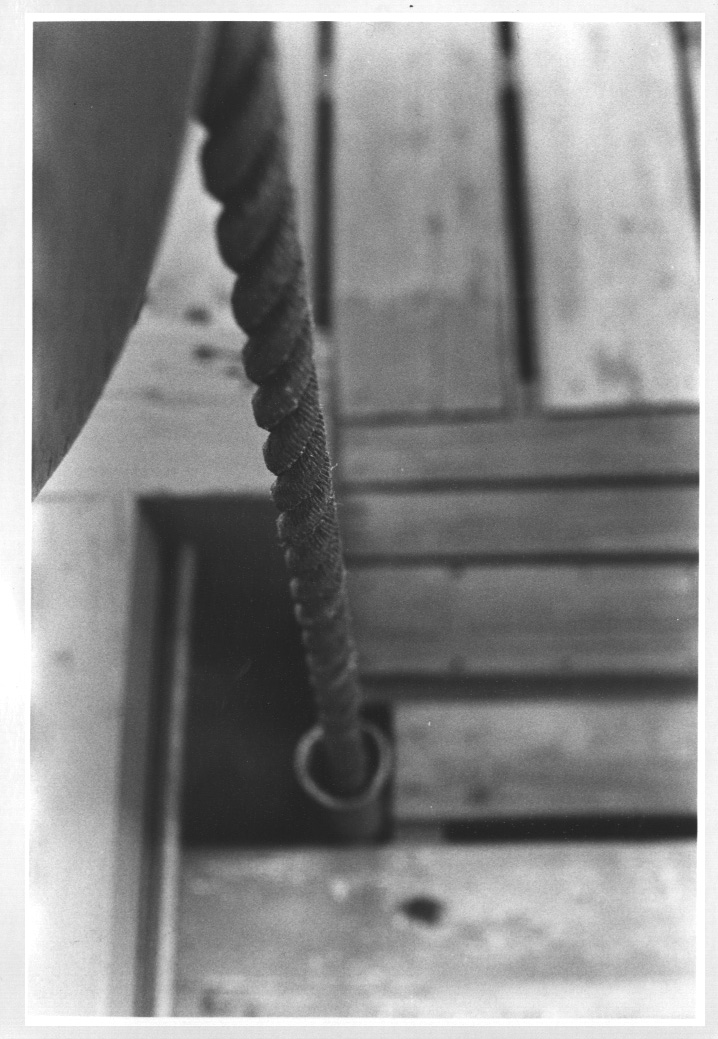

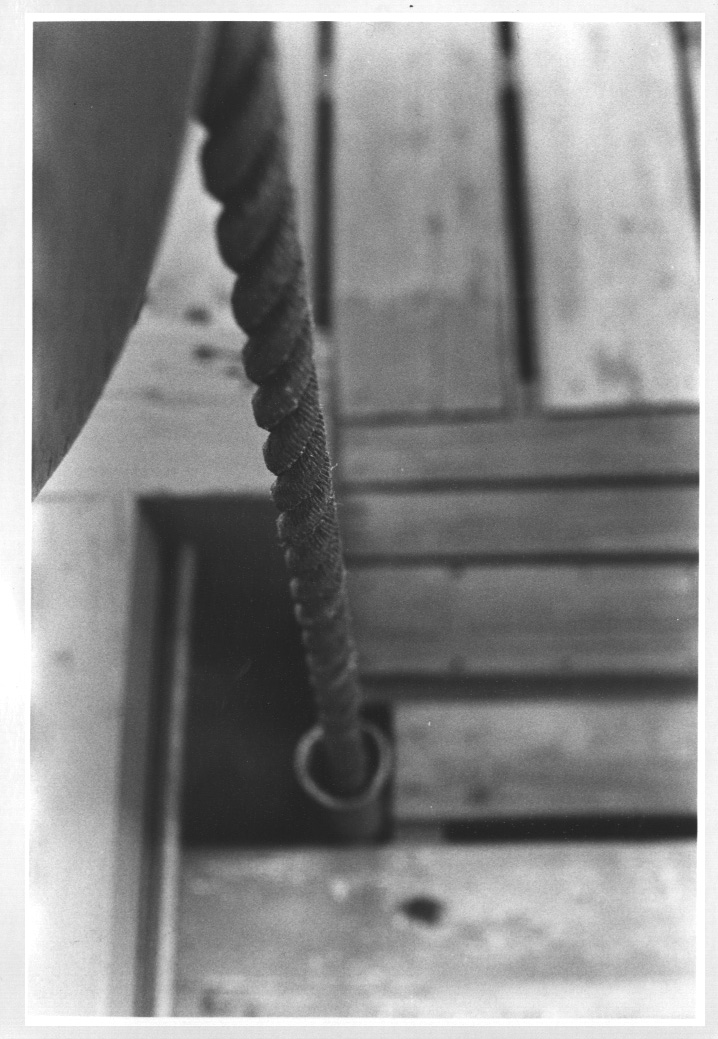

"The hammer strikes every hour, but we still pull at noon and nine," said Bert. "So, at noon, the hammer strikes twelve times, and then we pull the rope thirty times. That's 60 rings because the bell swings back and forth on one pull. That's how we get the 72." It had been just about as he said this that the noontime tones had begun. I had listened with uncovered ears to the full impact of the bell, and the following 30 pulls by Bert. There was a heavy vibration in the air, and yet the sound after sound began to seem softer and softer to me, almost as though it was moving in to my muffling mind.. "The hammer strikes every hour, but we still pull at noon and nine," said Bert. "So, at noon, the hammer strikes twelve times, and then we pull the rope thirty times. That's 60 rings because the bell swings back and forth on one pull. That's how we get the 72." It had been just about as he said this that the noontime tones had begun. I had listened with uncovered ears to the full impact of the bell, and the following 30 pulls by Bert. There was a heavy vibration in the air, and yet the sound after sound began to seem softer and softer to me, almost as though it was moving in to my muffling mind..

The full sound, the full richness must be felt to really be appreciated. Hearing it, is only part of it. It was truly pleasurable to stand within a few feet of the bell while it pealed. The tones were deep and metalic, yet rich and robustly exciting. They seemed to go on and on, blending together into a single sound. I anticipated each one, not cringing, but really embracing them, relishing them, wishing they would never end. As the pealing continued it became one long tonal vibration with ups and downs almost as if the bell were deeply singing to me. And, my ears were still ringing long after the noontime pull came to an end. Bert was laughing. He was thoroughly enjoying himself, obviously. "I've done it a thousand times and I still love it."

"You ring it some other times, too? Right, Bert?"

"Yes. On the Fourth Of July, of course. We ring it at 7:30

A.M., 12 Noon, and, again at 6:00 P.M. We pull the rope  for 30 minutes each time, who knows how many rings? And, then on Washington's Birthday we do the same thing. On November 11th we ring it for five minutes at those same times. For Town Meeting we ring it at 7:00 P.M. for five minutes and then again at 7:30 P.M. for another 5 minutes. And then, on special occasions, as decided by The Board Of Selectmen, we ring it however long they tell us. Like on the 200th Anniversary of the Constitution of the United States we rang it for two and a half minutes. for 30 minutes each time, who knows how many rings? And, then on Washington's Birthday we do the same thing. On November 11th we ring it for five minutes at those same times. For Town Meeting we ring it at 7:00 P.M. for five minutes and then again at 7:30 P.M. for another 5 minutes. And then, on special occasions, as decided by The Board Of Selectmen, we ring it however long they tell us. Like on the 200th Anniversary of the Constitution of the United States we rang it for two and a half minutes.

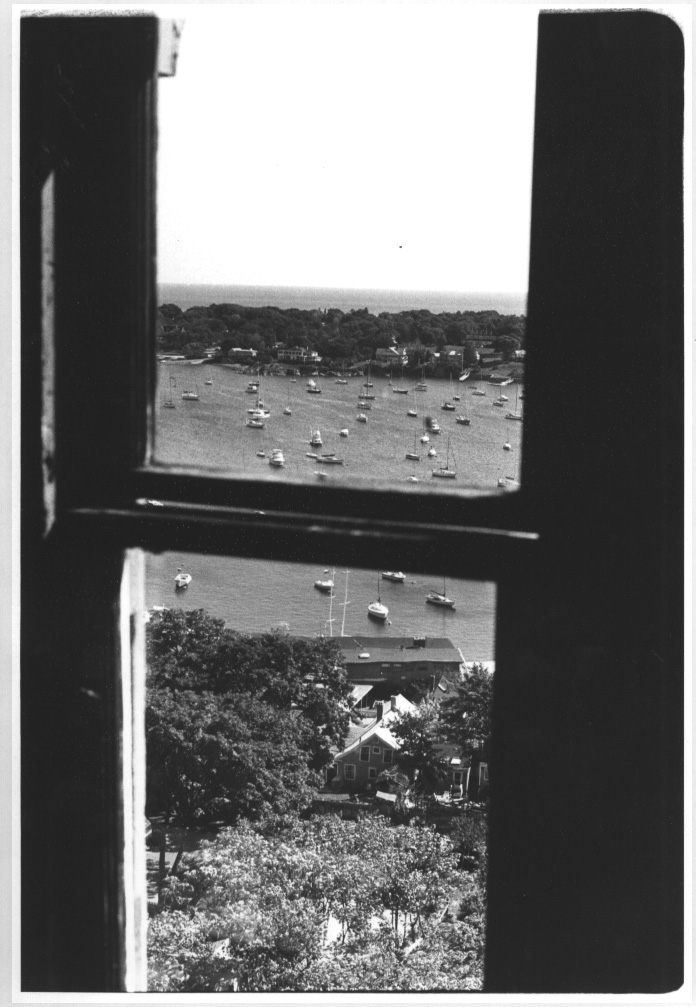

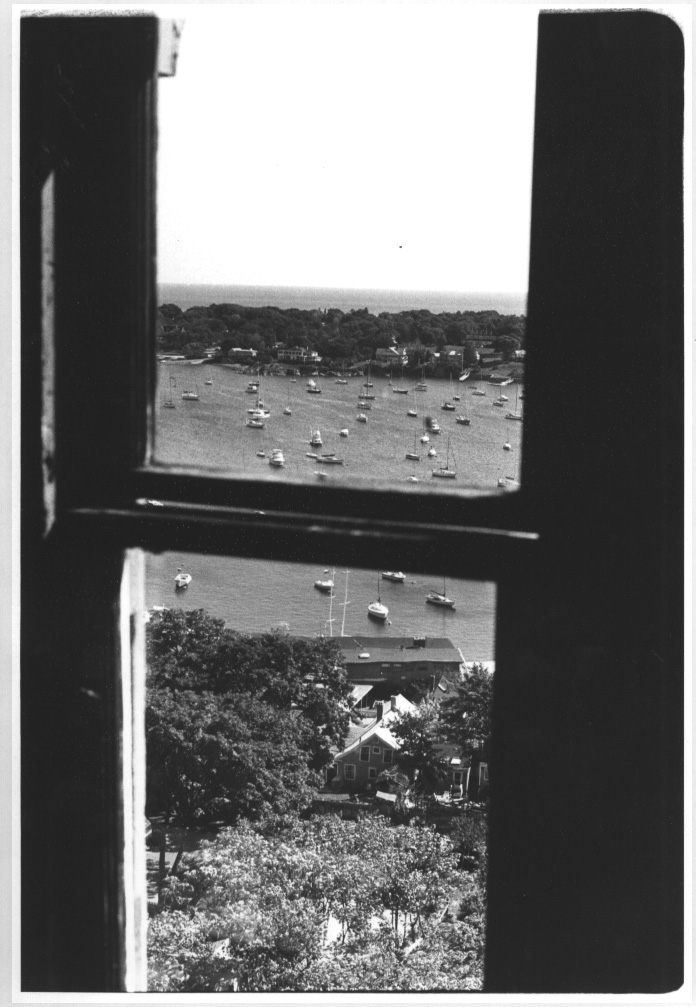

The cool Autumn breeze was blowing off the harbor and in and out of the belfry's four openings as we stood there discussing these things. The soft winds had the slight cool touch of a coming winter as they came in one side and went out the other, touching us and ruffling our clothes. Bert held onto his hat. The floorboard creaked a little as the bell slowed down and settled in its cradle, finally hanging motionless there, tilted as it always is, waiting for the next pull. The cool Autumn breeze was blowing off the harbor and in and out of the belfry's four openings as we stood there discussing these things. The soft winds had the slight cool touch of a coming winter as they came in one side and went out the other, touching us and ruffling our clothes. Bert held onto his hat. The floorboard creaked a little as the bell slowed down and settled in its cradle, finally hanging motionless there, tilted as it always is, waiting for the next pull.

Standing beside the bell, there in the tower, Abbot Hall seemed to have time travelled directly from the past with its messages of hope and citizenry and of good old Marblehead. It was as though it were still 1876 and we were  those first Marbleheaders who had come up to the tower and see the bell and to feel its power. Everything was exactly the same up there. I reached out and touched the bell. The metal was cold and hard. Inside it there were still small vibrations I could feel fading away slowly. In the quiet of the tower and the harbor breezes, the Bell of Abbot Hall was still ringing silently to itself like a voice whispering a faint message from the past. If we could only hear it. those first Marbleheaders who had come up to the tower and see the bell and to feel its power. Everything was exactly the same up there. I reached out and touched the bell. The metal was cold and hard. Inside it there were still small vibrations I could feel fading away slowly. In the quiet of the tower and the harbor breezes, the Bell of Abbot Hall was still ringing silently to itself like a voice whispering a faint message from the past. If we could only hear it.

On the way back down the ladder, I used the top of my head to

push up on the trapdoor, just a little, to ease the hasp on the

staple and secure the old padlock it its place. Bert showed me

how to do this and how to be sure that the lock was safely seated.

Moving on down, I rubbed the top of my head where the heavy door

had been. He said, smiling, "it's heavy, isn't it?" I had inadvertently

joined a small fraternity of Marbleheaders who had done that exact same

thing over the many years. When

we finally reached the bottom, I said thanks to Bert and shook

his hand and we both looked back up at the tower for another

second or two.

Just when I reached my car, the clock struck one.

|